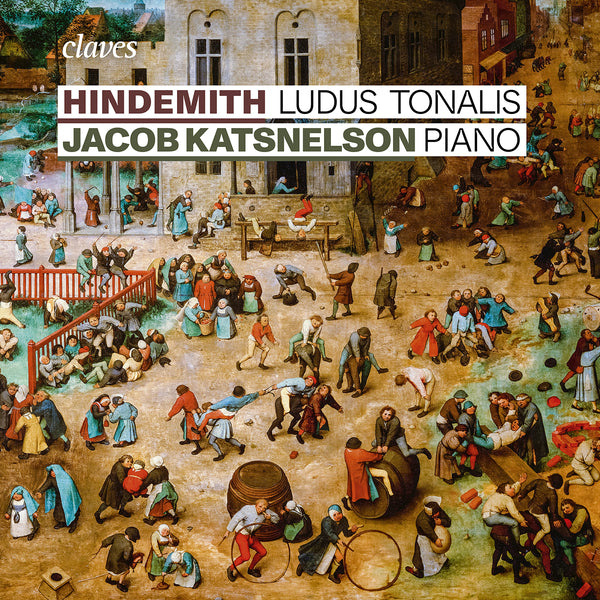

(2025) Ludus Tonalis

Category(ies): Piano Repertoire

Instrument(s): Piano

Main Composer: Paul Hindemith

CD set: 1

Catalog N°:

CD 3106

Release: 12.09.2025

EAN/UPC: 7619931310626

This album is now on repressing. Pre-order it at a special price now.

CHF 18.50

This album is no longer available on CD.

This album has not been released yet. Pre-order it from now.

CHF 18.50

This album is no longer available on CD.

CHF 18.50

VAT included for Switzerland & UE

Free shipping

This album is no longer available on CD.

VAT included for Switzerland & UE

Free shipping

This album is now on repressing. Pre-order it at a special price now.

CHF 18.50

This album is no longer available on CD.

This album has not been released yet.

Pre-order it at a special price now.

CHF 18.50

This album is no longer available on CD.

CHF 18.50

This album is no longer available on CD.

LUDUS TONALIS

I love Hindemith's music for its unique “harmony of the world” (Harmonie der Welt).

It is as diverse and unique as life itself. But it also has many parallels with different musical trends from different eras, from Renaissance polyphony to the lyrical works of Romanticism. I feel particularly close to the influences of Schubert, Schumann, and Brahms.

PAUL HINDEMITH: LUDUS TONALIS

Hindemith’s Ludus tonalis. Studies in Counterpoint, Tonal Organisation & Piano Playing was composed in the summer and autumn of 1942, at a time when the composer had already been living in exile in the United States for two years. His life had changed drastically since 1933 due to the political situation in Germany, ultimately forcing him to emigrate. Whereas he had been one of the most important representatives of the young generation of composers in Germany in the 1920s, his works were now defamed as ‘cultural Bolshevism’ and no longer performed; he received no more concert engagements in Germany. During these years of limited concert activity, Hindemith devoted himself intensively to music theory and composition in addition to composing chamber music. In 1937, he published his first major theoretical work, Unterweisung im Tonsatz (The Craft of Musical Composition).

In 1940, Paul Hindemith began teaching at Yale University in New Haven, cementing his reputation as an internationally renowned composer and soon becoming one of the leading composition teachers in the United States. However, with the USA’s entry into the war at the end of 1941, the musician’s position changed once again: in a climate of national exuberance and solidarity with Germany’s enemies, the works of American and Soviet composers came to the fore. In July 1942, a performance of Dmitri Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony, conducted by Arturo Toscanini, became a spectacular event in New York. The symphony had been written in Leningrad, a city under siege by German troops. On the other hand, artists who had emigrated from Germany were increasingly marginalised. Hindemith was embittered by these developments, as can be seen from a letter to his American publisher in November 1942: On the other hand, I believe that today, when every immature coward writes his own symphony and every conductor performs the most utter rubbish because he is either American or Russian and has no other merits except that he is currently set for orchestral performance; where, moreover, music seems to be judged solely by the extent to which it affects the common sensory organs between the pineal gland and the prostate, that something must appear at this very moment to show those who have not yet slipped irretrievably what music and composition are. [...] and I also know that it is entirely irrelevant to the current state of the world whether the siege of Leningrad depicted in symphonies is confronted with a moral (albeit only properly appreciated after 50 [...] years) conquest.

What is music and what is composition: this is what Hindemith intended to demonstrate in Ludus tonalis, his last work for piano solo, which was about to go to press at the time. His thoughts on harmony and composition, set out in Unterweisung im Tonsatz (The Craft of Musical Composition), found direct application in the final conception of Ludus tonalis.

However, Hindemith had probably not envisaged such a sophisticated cycle in terms of form and harmony when he began composing the first fugue on 29 August 1942. In his handwritten catalogue of works, he called them little three-part fugues for piano. Sketches reveal that he originally intended to arrange them in a chromatic sequence of keys, i.e. from C to D flat, D, and so forth. Only in the course of further work on the piece did the idea mature to devise a large-scale cycle of piano pieces whose formal and compositional structure would do justice to the principles set out in his theoretical writings.

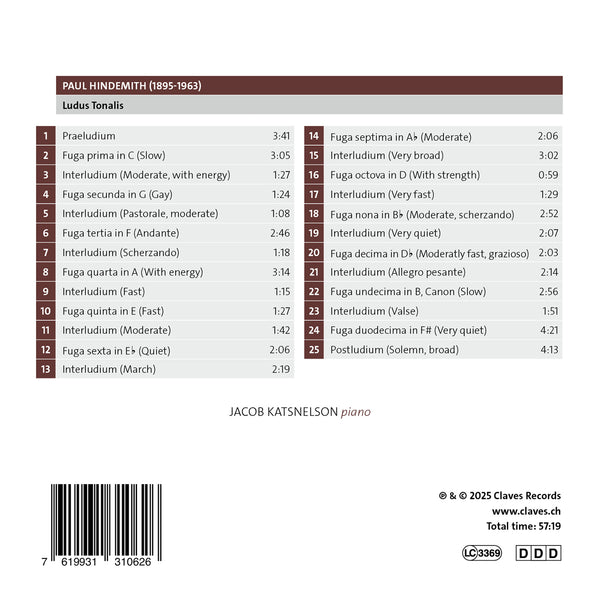

In The Craft of Musical Composition, Hindemith derived relationships between the twelve tones of the chromatic scale corresponding to the structure of the overtone series: the closest relationship is that of the fifth interval, the most distant the tritone. This results in a sequence of 12 tones, always based on C, which Hindemith called Series 1: C - G - F - A - E - E flat - A flat - D - B - D flat - B - F sharp. The twelve fugues of the Ludus tonalis are arranged in this order according to their tonalities.

Two further fundamental principles of Hindemith’s harmony and composition theory are fulfilled in Ludus tonalis: in accordance with his belief that major-minor polarity does not exist, Hindemith composed not twenty-four but twelve fugues, which are specified by their respective fundamental tone: Fuga prima in C, Fuga secunda in G, Fuga tertia in F, etc. All the fugues are also written for three voices. Hindemith was convinced that a maximum of three independent voices can be perceived separately; on the other hand, only three-part writing enables an unambiguous tonal assignment of the piece.

Immediately after completing the fugues, Hindemith began composing mid-September 1942 the eleven interludes (Interludium) and the Praeludium and Postludium. The interludes, conceived in completely free form, serve as mediators between the keys of the respective fugues. They modulate (with a few exceptions) from the tonic of the preceding fugue to that of the next. Hindemith conceived the interludes as character pieces, although only the interludes 2 (Pastorale), 6 (March) and 11 (Waltz) bear corresponding titles.

The conception of the Praelidium required in particular great artistry: if one turns around the score by 180°, one obtains the Postludium, which is thus the reverse inversion of the Praeludium. The Praeludium is structured in three parts. An introductory section, which covers almost the entire range of the instrument in a toccata-like fashion, is followed by a three-part arioso with a lyrical melody. The Praeludium concludes with a passage marked solemn, broad, based on a bass ostinato repeated six times. The Praeludium begins in C and leads to F sharp at the beginning of the ostinato, thus already establishing the tonal framework of the following fugue cycle.

Ludus tonalis was premiered with great success in Chicago on 15 February 1944 by Willard McGregor. The score went on sale during the final months of the war in Germany, from where Willy Strecker, Hindemith’s publisher, reported to the composer in the summer of 1946: Your piano sonatas and “Ludus” are being performed a great deal.

The fascination exerted by this work – which despite all its artifice and construction achieves the highest degree of musical expressiveness – was put in words by one of the first to encounter it, the composer Fritz von Borries, to whom Willy Strecker had already sent the piece in the summer of 1944: [...] What has here become music is not a mathematical problem or experiment, but a deep spiritual triumph, in which ultimate reason and ultimate being are revealed. How can the meaning of Praeludium and Postludium be more clearly represented than by letting that which began in the beginning appear in the end and run its course in reverse direction and vertically inverted? And what wonderful music it is both times.

Dr. Susanne Schaal-Gotthardt

Director of the Hindemith Institute Frankfurt

Translation: Michelle Bulloch – Musitext

Jacob Katsnelson

Born 1976 in Moscow, Jacob Katsnelson displayed exceptional musical talent at a very early age, entering the Music School for Gifted Children of the famed Gnessin Institute at five in 1981. Choosing to specialize in flute and piano he obtained diplomas with “highest distinction” in both instruments in 1993; and thereafter continued studies in the master class of the renowned pianist Elisso Virsaladze at the Tchaikovsky Conservatory in Moscow.

In 1992 he obtained a distinction in the Russian Competition for Young Musicians as well as in the 10th International Competition J. S. Bach in Leipzig (1996). In 1999 he was finalist at the Concours Musical International Reine Elisabeth de Belgique in Brussels; and in 2000 semifinalist at the Concours Géza Anda in Zurich. In 2001 he was a laureate of the International Piano Competition in Tbilisi (Georgia) where he also received the Special Prize for the Best Interpretation of a Work by Beethoven. In 2003 he was one of three finalists at the Concours International de Piano Clara Haskil in Vevey (Switzerland) and in 2005 obtained second prize at the First International Piano Competition Sviatoslav Richter in Moscow.

He also formed the piano trio Akadem which won first prize at the 1999 Taneyev Chamber Music Competition in Kaluga (Russia) and in 2000, second prize at the International Chamber Music Competition in Trapani (Sicily).

He has performed recitals and chamber music concerts in Russia (e.g. each year at the ”Homecoming Festival” in Moscow), Germany, Belgium, Holland (Kamermuziek Festival Utrecht with Janine Jansen, Boris Brovtsyn, Maxim Rysanov, Misha Maisky, etc.), France, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, Northern Ireland, USA, Spain, Italy, Hungary, Estonia (Festival Hiiumaa), Latvia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Bosnia, Israel… He has also appeared as soloist with well known orchestras such as the Philharmonic Orchestra of Saratov in Moscow, and those of Nizhny Novgorod, Saint-Petersburg, Brussels, Switzerland, Georgia, Chisinau/Moldavia, Baku/Azerbaijan, Rhodes.

Besides many life records in the concert halls of Tchaikovsky Conservatory Jacob Katsnelson produced a CD with Kristine Blaumane, cello, featuring compositions of S. Barber, E. Grieg and B. Martinu; another one with the violist Maxim Rysanov playing Brahms. His CD with solo works of J. S. Bach appeared recently under the label Quartz (QTZ 2084).

Jacob Katsnelson is professor at the Tchaikovsky Conservatory in Moscow and teaches lieder interpretation at the Gnessin Institute in Moscow.

REVIEWS

"Composé aux Etats-Unis en 1942, le Ludus tonalis (douze préludes et fugues, garnis d’un postlude qui renverse le prélude initial) souffre d’une réputation tenace d’austérité rébarbative. Et si le cycle est une sorte d’hommage à Bach, Hindemith y déploie une incroyable maîtrise du contrepoint sans rien abdiquer des sa personnalité. Les préludes sont d’une fantaisie et d’une inventivité débridées. En forme ici de marche, là de valse, tout à tour lents ou rapides, ils témoignent d’une imagination vive et même d’un humour insoupçonné. [..]" - Jean-Claude Hulot, novembre 2025

"Le recueil "Ludus Tonalis" (Studies in counterpoint Tonal organisation & piano playing) fut composé par Paul Hindemith en 1942 alors que ce dernier s’est exilé pendant deux ans aux Etats-Unis, suite à la funeste situation politique en Allemagne. [..] Sans égaler le toucher marmoréen de Boris Berezovsky (Teldec) le pianiste russe Jacob Kastnelson aborde l’ouvrage avec une belle autorité et un sens naturel de la polyphonie." - Jean-Claude Hulot, novembre 2025

(2025) Ludus Tonalis - CD 3106

I love Hindemith's music for its unique “harmony of the world” (Harmonie der Welt).

It is as diverse and unique as life itself. But it also has many parallels with different musical trends from different eras, from Renaissance polyphony to the lyrical works of Romanticism. I feel particularly close to the influences of Schubert, Schumann, and Brahms.

PAUL HINDEMITH: LUDUS TONALIS

Hindemith’s Ludus tonalis. Studies in Counterpoint, Tonal Organisation & Piano Playing was composed in the summer and autumn of 1942, at a time when the composer had already been living in exile in the United States for two years. His life had changed drastically since 1933 due to the political situation in Germany, ultimately forcing him to emigrate. Whereas he had been one of the most important representatives of the young generation of composers in Germany in the 1920s, his works were now defamed as ‘cultural Bolshevism’ and no longer performed; he received no more concert engagements in Germany. During these years of limited concert activity, Hindemith devoted himself intensively to music theory and composition in addition to composing chamber music. In 1937, he published his first major theoretical work, Unterweisung im Tonsatz (The Craft of Musical Composition).

In 1940, Paul Hindemith began teaching at Yale University in New Haven, cementing his reputation as an internationally renowned composer and soon becoming one of the leading composition teachers in the United States. However, with the USA’s entry into the war at the end of 1941, the musician’s position changed once again: in a climate of national exuberance and solidarity with Germany’s enemies, the works of American and Soviet composers came to the fore. In July 1942, a performance of Dmitri Shostakovich’s Seventh Symphony, conducted by Arturo Toscanini, became a spectacular event in New York. The symphony had been written in Leningrad, a city under siege by German troops. On the other hand, artists who had emigrated from Germany were increasingly marginalised. Hindemith was embittered by these developments, as can be seen from a letter to his American publisher in November 1942: On the other hand, I believe that today, when every immature coward writes his own symphony and every conductor performs the most utter rubbish because he is either American or Russian and has no other merits except that he is currently set for orchestral performance; where, moreover, music seems to be judged solely by the extent to which it affects the common sensory organs between the pineal gland and the prostate, that something must appear at this very moment to show those who have not yet slipped irretrievably what music and composition are. [...] and I also know that it is entirely irrelevant to the current state of the world whether the siege of Leningrad depicted in symphonies is confronted with a moral (albeit only properly appreciated after 50 [...] years) conquest.

What is music and what is composition: this is what Hindemith intended to demonstrate in Ludus tonalis, his last work for piano solo, which was about to go to press at the time. His thoughts on harmony and composition, set out in Unterweisung im Tonsatz (The Craft of Musical Composition), found direct application in the final conception of Ludus tonalis.

However, Hindemith had probably not envisaged such a sophisticated cycle in terms of form and harmony when he began composing the first fugue on 29 August 1942. In his handwritten catalogue of works, he called them little three-part fugues for piano. Sketches reveal that he originally intended to arrange them in a chromatic sequence of keys, i.e. from C to D flat, D, and so forth. Only in the course of further work on the piece did the idea mature to devise a large-scale cycle of piano pieces whose formal and compositional structure would do justice to the principles set out in his theoretical writings.

In The Craft of Musical Composition, Hindemith derived relationships between the twelve tones of the chromatic scale corresponding to the structure of the overtone series: the closest relationship is that of the fifth interval, the most distant the tritone. This results in a sequence of 12 tones, always based on C, which Hindemith called Series 1: C - G - F - A - E - E flat - A flat - D - B - D flat - B - F sharp. The twelve fugues of the Ludus tonalis are arranged in this order according to their tonalities.

Two further fundamental principles of Hindemith’s harmony and composition theory are fulfilled in Ludus tonalis: in accordance with his belief that major-minor polarity does not exist, Hindemith composed not twenty-four but twelve fugues, which are specified by their respective fundamental tone: Fuga prima in C, Fuga secunda in G, Fuga tertia in F, etc. All the fugues are also written for three voices. Hindemith was convinced that a maximum of three independent voices can be perceived separately; on the other hand, only three-part writing enables an unambiguous tonal assignment of the piece.

Immediately after completing the fugues, Hindemith began composing mid-September 1942 the eleven interludes (Interludium) and the Praeludium and Postludium. The interludes, conceived in completely free form, serve as mediators between the keys of the respective fugues. They modulate (with a few exceptions) from the tonic of the preceding fugue to that of the next. Hindemith conceived the interludes as character pieces, although only the interludes 2 (Pastorale), 6 (March) and 11 (Waltz) bear corresponding titles.

The conception of the Praelidium required in particular great artistry: if one turns around the score by 180°, one obtains the Postludium, which is thus the reverse inversion of the Praeludium. The Praeludium is structured in three parts. An introductory section, which covers almost the entire range of the instrument in a toccata-like fashion, is followed by a three-part arioso with a lyrical melody. The Praeludium concludes with a passage marked solemn, broad, based on a bass ostinato repeated six times. The Praeludium begins in C and leads to F sharp at the beginning of the ostinato, thus already establishing the tonal framework of the following fugue cycle.

Ludus tonalis was premiered with great success in Chicago on 15 February 1944 by Willard McGregor. The score went on sale during the final months of the war in Germany, from where Willy Strecker, Hindemith’s publisher, reported to the composer in the summer of 1946: Your piano sonatas and “Ludus” are being performed a great deal.

The fascination exerted by this work – which despite all its artifice and construction achieves the highest degree of musical expressiveness – was put in words by one of the first to encounter it, the composer Fritz von Borries, to whom Willy Strecker had already sent the piece in the summer of 1944: [...] What has here become music is not a mathematical problem or experiment, but a deep spiritual triumph, in which ultimate reason and ultimate being are revealed. How can the meaning of Praeludium and Postludium be more clearly represented than by letting that which began in the beginning appear in the end and run its course in reverse direction and vertically inverted? And what wonderful music it is both times.

Dr. Susanne Schaal-Gotthardt

Director of the Hindemith Institute Frankfurt

Translation: Michelle Bulloch – Musitext

Jacob Katsnelson

Born 1976 in Moscow, Jacob Katsnelson displayed exceptional musical talent at a very early age, entering the Music School for Gifted Children of the famed Gnessin Institute at five in 1981. Choosing to specialize in flute and piano he obtained diplomas with “highest distinction” in both instruments in 1993; and thereafter continued studies in the master class of the renowned pianist Elisso Virsaladze at the Tchaikovsky Conservatory in Moscow.

In 1992 he obtained a distinction in the Russian Competition for Young Musicians as well as in the 10th International Competition J. S. Bach in Leipzig (1996). In 1999 he was finalist at the Concours Musical International Reine Elisabeth de Belgique in Brussels; and in 2000 semifinalist at the Concours Géza Anda in Zurich. In 2001 he was a laureate of the International Piano Competition in Tbilisi (Georgia) where he also received the Special Prize for the Best Interpretation of a Work by Beethoven. In 2003 he was one of three finalists at the Concours International de Piano Clara Haskil in Vevey (Switzerland) and in 2005 obtained second prize at the First International Piano Competition Sviatoslav Richter in Moscow.

He also formed the piano trio Akadem which won first prize at the 1999 Taneyev Chamber Music Competition in Kaluga (Russia) and in 2000, second prize at the International Chamber Music Competition in Trapani (Sicily).

He has performed recitals and chamber music concerts in Russia (e.g. each year at the ”Homecoming Festival” in Moscow), Germany, Belgium, Holland (Kamermuziek Festival Utrecht with Janine Jansen, Boris Brovtsyn, Maxim Rysanov, Misha Maisky, etc.), France, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, Northern Ireland, USA, Spain, Italy, Hungary, Estonia (Festival Hiiumaa), Latvia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Bosnia, Israel… He has also appeared as soloist with well known orchestras such as the Philharmonic Orchestra of Saratov in Moscow, and those of Nizhny Novgorod, Saint-Petersburg, Brussels, Switzerland, Georgia, Chisinau/Moldavia, Baku/Azerbaijan, Rhodes.

Besides many life records in the concert halls of Tchaikovsky Conservatory Jacob Katsnelson produced a CD with Kristine Blaumane, cello, featuring compositions of S. Barber, E. Grieg and B. Martinu; another one with the violist Maxim Rysanov playing Brahms. His CD with solo works of J. S. Bach appeared recently under the label Quartz (QTZ 2084).

Jacob Katsnelson is professor at the Tchaikovsky Conservatory in Moscow and teaches lieder interpretation at the Gnessin Institute in Moscow.

REVIEWS

"Composé aux Etats-Unis en 1942, le Ludus tonalis (douze préludes et fugues, garnis d’un postlude qui renverse le prélude initial) souffre d’une réputation tenace d’austérité rébarbative. Et si le cycle est une sorte d’hommage à Bach, Hindemith y déploie une incroyable maîtrise du contrepoint sans rien abdiquer des sa personnalité. Les préludes sont d’une fantaisie et d’une inventivité débridées. En forme ici de marche, là de valse, tout à tour lents ou rapides, ils témoignent d’une imagination vive et même d’un humour insoupçonné. [..]" - Jean-Claude Hulot, novembre 2025

"Le recueil "Ludus Tonalis" (Studies in counterpoint Tonal organisation & piano playing) fut composé par Paul Hindemith en 1942 alors que ce dernier s’est exilé pendant deux ans aux Etats-Unis, suite à la funeste situation politique en Allemagne. [..] Sans égaler le toucher marmoréen de Boris Berezovsky (Teldec) le pianiste russe Jacob Kastnelson aborde l’ouvrage avec une belle autorité et un sens naturel de la polyphonie." - Jean-Claude Hulot, novembre 2025

Return to the album | Read the booklet | Open online links | Composer(s): Paul Hindemith | Main Artist: Jacob Katsnelson