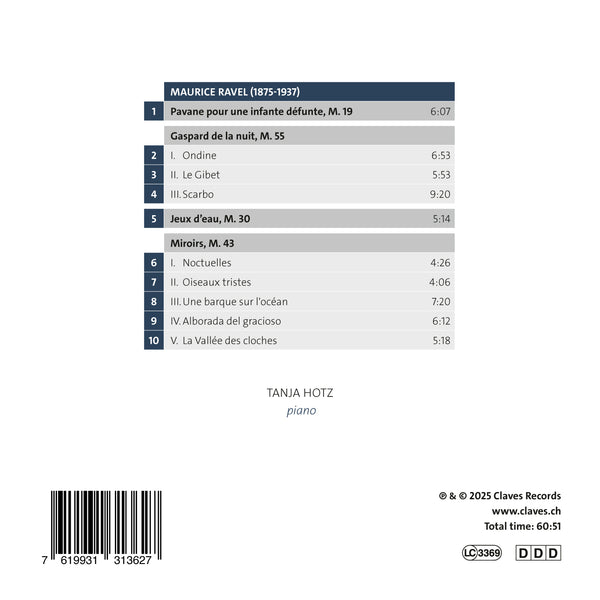

(2025) Ravel: Piano Works

Category(ies): Debut Piano

Instrument(s): Piano

Main Composer: Maurice Ravel

CD set: 1

Catalog N°:

CD 3136

Release: 31.10.2025

EAN/UPC: 7619931313627

This album is now on repressing. Pre-order it at a special price now.

CHF 18.50

This album is no longer available on CD.

This album has not been released yet. Pre-order it from now.

CHF 18.50

This album is no longer available on CD.

CHF 18.50

VAT included for Switzerland & UE

Free shipping

This album is no longer available on CD.

VAT included for Switzerland & UE

Free shipping

This album is now on repressing. Pre-order it at a special price now.

CHF 18.50

This album is no longer available on CD.

This album has not been released yet.

Pre-order it at a special price now.

CHF 18.50

This album is no longer available on CD.

CHF 18.50

This album is no longer available on CD.

RAVEL: PIANO WORKS

About this album

The piano music of Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) is often upheld alongside that of his contemporary Claude Debussy as quintessentially French and Impressionist. The reality is more complicated. Neither he nor Debussy were fond of the term ‘Impressionist’ at all, and although born in southern France, there wasn’t really much that was ‘French’ about Ravel. His father was Swiss (not for nothing did Stravinsky nickname Ravel a ‘Swiss clockmaker’) and his mother was Spanish Basque. If he’d been born eight kilometres further south, Spain could have claimed Ravel as her own. But the family moved to Paris just a few months after Maurice was born, which meant his musical upbringing benefited from everything that the capital could offer.

Ravel’s early teachers were all trained at the Paris Conservatoire – long one of Europe’s most august such institutions – and he himself was accepted into its ranks in November 1889. After initial successes, however, his results dwindled and he left in 1895; he returned two years later, but his problematic relationship with the institution did not improve. From 1900 to 1905 he failed five times to win the Prix de Rome that so many illustrious predecessors had won before him, from Hector Berlioz to Debussy. By the time of his final failure, however, he had already established such a reputation outside the Conservatoire that his elimination caused a major scandal, forcing the resignation of its Director.

Ravel’s Pavane for a dead infanta of 1899 is his earliest work to enter the repertoire, and it became so popular that he later claimed to dislike it. But it well deserves its fame, and in its apparent simplicity it foreshadows many aspects of the later Ravel, from its semi-modal air that keeps us guessing just which key we’re in, to its firm foundation in the bass – not to mention the manner in which Ravel can shift the meaning of a passage by repeating it with different harmony for the upper line.

Jeux d’eau (‘fountains’) was composed just two years later in 1901, but we are here presented with the mature Ravel almost as a fait accompli, with its coruscating, added major sixths and sevenths. Its model was Franz Liszt’s ‘Fountains of the Villa d’Este’ of 1882, whose piano arpeggios of bubbling water provided the prototype for all the water pieces of the early 20th century. And when Ravel was once asked how his piece should be played, he reputedly answered (no doubt sarcastically) ‘like Liszt’. But whereas the rapid figurations in Liszt are largely on the surface, Ravel’s textures are more complex. See, for example, the final two pages where the water ripples in right-hand arpeggios above a pentatonic melody in the middle of the keyboard while the bass line descends slowly and inexorably to the tonic. As Ravel himself later observed, it was his Jeux d’eau that gave Debussy and others a model of how their generation might utilise to the full the possibilities offered by the modern piano. It also gave other composers even further-reaching ideas – the central cadenza with its juxtaposition of C and F-sharp major sounds today remarkably prescient of Igor Stravinsky’s Petrushka.

In about 1902, Maurice Ravel joined a group of artists that called themselves Les Apaches (‘the ruffians’), and it was to them that he dedicated the five programmatic movements of his piano suite Miroirs of 1904-5. Noctuelles (‘Moths’) begins without any sense of tonality at all – parallel (broken) chords in triplets in the left hand accompanying a highly chromatic, rising sixteenth-note figure in the right. But it cadences clearly in D-flat major at the close, and like many of Ravel’s pieces (including Jeux d’eau), it is cast in an idiosyncratic sonata form. The second movement of Miroirs, ‘Sad birds’, and the fifth, ‘Valley of the bells’, were supposedly inspired by Ravel’s experience of Paris and its environs – respectively the forest of Fontainebleau, and the many midday bells of Paris itself (though the repeated G-sharp of Liszt’s La campanella also makes itself heard in the latter piece). No. 3, the ‘Boat on the ocean’ is arguably Ravel’s finest water piece – this time, it’s the sea and its swells he is depicting – while No. 4, the ‘Aubade of the jester’ is one of his many dance-like homages to the Spanish homeland of his mother, whose humour and apparent wild abandon are nevertheless contained in a form that Ravel once remarked was ‘as strict as a fugue by Bach’.

Ravel’s closest friend among the Apaches was a man he’d known since they were both in their teens: his Spanish contemporary the pianist Ricardo Viñes, who had also moved to Paris in his youth. Viñes knew all the leading composers of Paris, and it was he who later kept Ravel and Debussy abreast of each other’s work after their early friendship had cooled into rivalry on account of the partisanship of their respective adherents. It was also Viñes who indirectly inspired Ravel to his biggest, most ambitious work for piano by getting him acquainted with the collection of prose poems of Aloysius Bertrand (1807-1841) entitled Gaspard de la nuit. In 1908, Ravel composed three large-scale pieces based on its poems, which he published as a group under the same title as the original collection. These were Ondine, a water sprite; Le gibet (‘The gallows’) and Scarbo (an evil goblin). The music for Ondine is reminiscent of Ravel’s other ‘water’ pieces, albeit to a higher order of virtuosity (listen, for example, to how towards the close he once again creates a shimmering right-hand texture to accompany a modal melody in the middle of the keyboard, underpinned by a largely static bass). In the second piece, a repeated B-flat ostinato throughout lets us almost see the slowly rotting corpse of a hanged man (Ricardo Viñes complained to Ravel that the slow tempo he wanted would bore his audiences, but it is in fact integral to the impact of the piece). And Scarbo’s flamenco rhythms for the gesticulating, spinning hobgoblin take us once more into Spanish territory, though with a complexity of realisation that makes it one of the most notoriously difficult pieces in the whole piano repertoire. Each of these three pieces is again in a Ravelian version of sonata form, without any guarantee that the order of material in the exposition will be followed in the recapitulation. Ricardo Viñes had already given the first performances of Ravel’s Pavane, Jeux d’eau and Miroirs, and he premièred Gaspard de la nuit too, in January 1909 in the Salle Érard in Paris.

In its compositional sophistication and sheer virtuosity, Gaspard de la nuit marked the highpoint of Ravel’s oeuvre for solo piano. His remaining few solo piano works revealed a more neo-classical trend, and his main focus now turned instead to the orchestra, to ballet and opera – with the piano making a final, triumphant return twenty years after Gaspard in his two concertos for the instrument.

Chris Walton

TANJA HOTZ

The Swiss-Icelandic pianist Tanja Hotz was born in Haifa, Israel and grew up in the canton of Zug in Switzerland. She received piano lessons from her mother at an early age and made her first attempts at composing.

From the age of seven, she studied with Madeleine Hoppe-Nussbaumer at the Music School of the City of Zug. In addition to piano, she also devoted herself to the violin, flute, voice and cello, as well as to music theory and composition. She took part in masterclasses in piano, composition and chamber music. She won several prizes at the Swiss Youth Music Competition in both piano and composition.

After graduating from high school, she continued her piano studies, this time with Adrian Oetiker at the Basel Academy of Music. She additionally studied composition with Georg Friedrich Haas and improvisation with Rudolf Lutz. In 2014, Tanja completed her bachelor’s degree with distinction. This was followed by a master’s degree in Piano Performance at the University of Music and Theatre Munich, which she completed in 2016 where she achieved top marks. She continued and furthered her studies in composition and music theory with Martin Lichtfuss at the University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna, where she also deepened her pianistic training with Lilya Zilberstein.

Beyond her music, Tanja also finds expression in the visual arts. Inspired by nature, she photographs, draws and paints – often guided by forms, colors and structures she observes in the natural environment. A particular focus of her artistic work lies in her interdisciplinary approach: She combines interpretation, composition and visual art. As part of her master’s project at the Zurich University of the Arts – where she completed her Master’s degree in music education mentored by Eckart Heiligers in 2020 – she organised a concert that combined music, poetry and painting by performing Maurice Ravel’s Gaspard de la Nuit and Robert Schumann’s Symphonic Etudes, accompanied by a presentation of her own thematic paintings.

Tanja Hotz has been sharing her passion and knowledge as a piano teacher at the Basel Academy of Music since August 2020.

REVIEWS

"Le principal attrait des Ravel de Tanja Hotz? Un Steinway splendide, auquel la captation donne une belle présence. La Pavane déploie des merveilles de séduction et, d'un allant inhabituel, Jeux d'eau dégage une fébrilité stimulante. [..]" - Bertrand Boissard, Décembre 2025

(2025) Ravel: Piano Works - CD 3136

About this album

The piano music of Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) is often upheld alongside that of his contemporary Claude Debussy as quintessentially French and Impressionist. The reality is more complicated. Neither he nor Debussy were fond of the term ‘Impressionist’ at all, and although born in southern France, there wasn’t really much that was ‘French’ about Ravel. His father was Swiss (not for nothing did Stravinsky nickname Ravel a ‘Swiss clockmaker’) and his mother was Spanish Basque. If he’d been born eight kilometres further south, Spain could have claimed Ravel as her own. But the family moved to Paris just a few months after Maurice was born, which meant his musical upbringing benefited from everything that the capital could offer.

Ravel’s early teachers were all trained at the Paris Conservatoire – long one of Europe’s most august such institutions – and he himself was accepted into its ranks in November 1889. After initial successes, however, his results dwindled and he left in 1895; he returned two years later, but his problematic relationship with the institution did not improve. From 1900 to 1905 he failed five times to win the Prix de Rome that so many illustrious predecessors had won before him, from Hector Berlioz to Debussy. By the time of his final failure, however, he had already established such a reputation outside the Conservatoire that his elimination caused a major scandal, forcing the resignation of its Director.

Ravel’s Pavane for a dead infanta of 1899 is his earliest work to enter the repertoire, and it became so popular that he later claimed to dislike it. But it well deserves its fame, and in its apparent simplicity it foreshadows many aspects of the later Ravel, from its semi-modal air that keeps us guessing just which key we’re in, to its firm foundation in the bass – not to mention the manner in which Ravel can shift the meaning of a passage by repeating it with different harmony for the upper line.

Jeux d’eau (‘fountains’) was composed just two years later in 1901, but we are here presented with the mature Ravel almost as a fait accompli, with its coruscating, added major sixths and sevenths. Its model was Franz Liszt’s ‘Fountains of the Villa d’Este’ of 1882, whose piano arpeggios of bubbling water provided the prototype for all the water pieces of the early 20th century. And when Ravel was once asked how his piece should be played, he reputedly answered (no doubt sarcastically) ‘like Liszt’. But whereas the rapid figurations in Liszt are largely on the surface, Ravel’s textures are more complex. See, for example, the final two pages where the water ripples in right-hand arpeggios above a pentatonic melody in the middle of the keyboard while the bass line descends slowly and inexorably to the tonic. As Ravel himself later observed, it was his Jeux d’eau that gave Debussy and others a model of how their generation might utilise to the full the possibilities offered by the modern piano. It also gave other composers even further-reaching ideas – the central cadenza with its juxtaposition of C and F-sharp major sounds today remarkably prescient of Igor Stravinsky’s Petrushka.

In about 1902, Maurice Ravel joined a group of artists that called themselves Les Apaches (‘the ruffians’), and it was to them that he dedicated the five programmatic movements of his piano suite Miroirs of 1904-5. Noctuelles (‘Moths’) begins without any sense of tonality at all – parallel (broken) chords in triplets in the left hand accompanying a highly chromatic, rising sixteenth-note figure in the right. But it cadences clearly in D-flat major at the close, and like many of Ravel’s pieces (including Jeux d’eau), it is cast in an idiosyncratic sonata form. The second movement of Miroirs, ‘Sad birds’, and the fifth, ‘Valley of the bells’, were supposedly inspired by Ravel’s experience of Paris and its environs – respectively the forest of Fontainebleau, and the many midday bells of Paris itself (though the repeated G-sharp of Liszt’s La campanella also makes itself heard in the latter piece). No. 3, the ‘Boat on the ocean’ is arguably Ravel’s finest water piece – this time, it’s the sea and its swells he is depicting – while No. 4, the ‘Aubade of the jester’ is one of his many dance-like homages to the Spanish homeland of his mother, whose humour and apparent wild abandon are nevertheless contained in a form that Ravel once remarked was ‘as strict as a fugue by Bach’.

Ravel’s closest friend among the Apaches was a man he’d known since they were both in their teens: his Spanish contemporary the pianist Ricardo Viñes, who had also moved to Paris in his youth. Viñes knew all the leading composers of Paris, and it was he who later kept Ravel and Debussy abreast of each other’s work after their early friendship had cooled into rivalry on account of the partisanship of their respective adherents. It was also Viñes who indirectly inspired Ravel to his biggest, most ambitious work for piano by getting him acquainted with the collection of prose poems of Aloysius Bertrand (1807-1841) entitled Gaspard de la nuit. In 1908, Ravel composed three large-scale pieces based on its poems, which he published as a group under the same title as the original collection. These were Ondine, a water sprite; Le gibet (‘The gallows’) and Scarbo (an evil goblin). The music for Ondine is reminiscent of Ravel’s other ‘water’ pieces, albeit to a higher order of virtuosity (listen, for example, to how towards the close he once again creates a shimmering right-hand texture to accompany a modal melody in the middle of the keyboard, underpinned by a largely static bass). In the second piece, a repeated B-flat ostinato throughout lets us almost see the slowly rotting corpse of a hanged man (Ricardo Viñes complained to Ravel that the slow tempo he wanted would bore his audiences, but it is in fact integral to the impact of the piece). And Scarbo’s flamenco rhythms for the gesticulating, spinning hobgoblin take us once more into Spanish territory, though with a complexity of realisation that makes it one of the most notoriously difficult pieces in the whole piano repertoire. Each of these three pieces is again in a Ravelian version of sonata form, without any guarantee that the order of material in the exposition will be followed in the recapitulation. Ricardo Viñes had already given the first performances of Ravel’s Pavane, Jeux d’eau and Miroirs, and he premièred Gaspard de la nuit too, in January 1909 in the Salle Érard in Paris.

In its compositional sophistication and sheer virtuosity, Gaspard de la nuit marked the highpoint of Ravel’s oeuvre for solo piano. His remaining few solo piano works revealed a more neo-classical trend, and his main focus now turned instead to the orchestra, to ballet and opera – with the piano making a final, triumphant return twenty years after Gaspard in his two concertos for the instrument.

Chris Walton

TANJA HOTZ

The Swiss-Icelandic pianist Tanja Hotz was born in Haifa, Israel and grew up in the canton of Zug in Switzerland. She received piano lessons from her mother at an early age and made her first attempts at composing.

From the age of seven, she studied with Madeleine Hoppe-Nussbaumer at the Music School of the City of Zug. In addition to piano, she also devoted herself to the violin, flute, voice and cello, as well as to music theory and composition. She took part in masterclasses in piano, composition and chamber music. She won several prizes at the Swiss Youth Music Competition in both piano and composition.

After graduating from high school, she continued her piano studies, this time with Adrian Oetiker at the Basel Academy of Music. She additionally studied composition with Georg Friedrich Haas and improvisation with Rudolf Lutz. In 2014, Tanja completed her bachelor’s degree with distinction. This was followed by a master’s degree in Piano Performance at the University of Music and Theatre Munich, which she completed in 2016 where she achieved top marks. She continued and furthered her studies in composition and music theory with Martin Lichtfuss at the University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna, where she also deepened her pianistic training with Lilya Zilberstein.

Beyond her music, Tanja also finds expression in the visual arts. Inspired by nature, she photographs, draws and paints – often guided by forms, colors and structures she observes in the natural environment. A particular focus of her artistic work lies in her interdisciplinary approach: She combines interpretation, composition and visual art. As part of her master’s project at the Zurich University of the Arts – where she completed her Master’s degree in music education mentored by Eckart Heiligers in 2020 – she organised a concert that combined music, poetry and painting by performing Maurice Ravel’s Gaspard de la Nuit and Robert Schumann’s Symphonic Etudes, accompanied by a presentation of her own thematic paintings.

Tanja Hotz has been sharing her passion and knowledge as a piano teacher at the Basel Academy of Music since August 2020.

REVIEWS

"Le principal attrait des Ravel de Tanja Hotz? Un Steinway splendide, auquel la captation donne une belle présence. La Pavane déploie des merveilles de séduction et, d'un allant inhabituel, Jeux d'eau dégage une fébrilité stimulante. [..]" - Bertrand Boissard, Décembre 2025

Return to the album | Read the booklet | Open online links | Composer(s): Maurice Ravel | Main Artist: Tanja Hotz