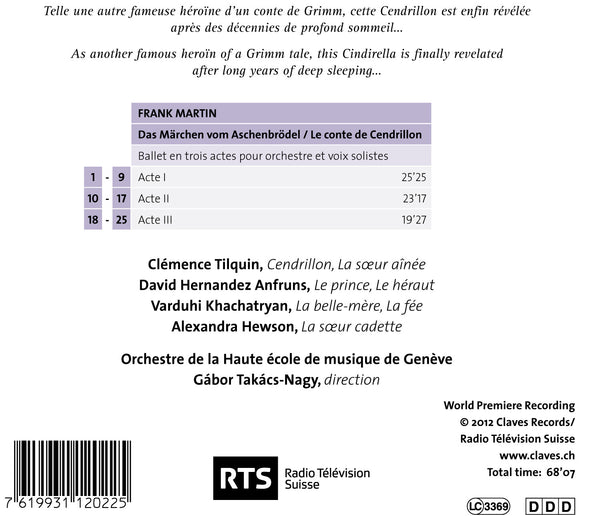

(2013) Frank Martin: Das Märchen vom Aschenbrödel (Le conte de Cendrillon)

Kategorie(n): Operngesang Orchester Raritäten

Hauptkomponist: Frank Martin

Orchester: Orchestre de la Haute Ecole de Musique de Genève

Dirigent: Gábor Takács-Nagy

CD-Set: 1

Katalog Nr.:

CD 1202

Freigabe: 01.01.2013

EAN/UPC: 7619931120225

- UPC: 887845252555

Dieses Album ist jetzt neu aufgelegt worden. Bestellen Sie es jetzt zum Sonderpreis vor.

CHF 18.50

Dieses Album ist nicht mehr auf CD erhältlich.

Dieses Album ist noch nicht veröffentlicht worden. Bestellen Sie es jetzt vor.

CHF 18.50

Dieses Album ist nicht mehr auf CD erhältlich.

CHF 18.50

Inklusive MwSt. für die Schweiz und die EU

Kostenloser Versand

Dieses Album ist nicht mehr auf CD erhältlich.

Inklusive MwSt. für die Schweiz und die EU

Kostenloser Versand

Dieses Album ist jetzt neu aufgelegt worden. Bestellen Sie es jetzt zum Sonderpreis vor.

CHF 18.50

Dieses Album ist nicht mehr auf CD erhältlich.

This album has not been released yet.

Pre-order it at a special price now.

CHF 18.50

Dieses Album ist nicht mehr auf CD erhältlich.

CHF 18.50

Dieses Album ist nicht mehr auf CD erhältlich.

SPOTIFY

(Verbinden Sie sich mit Ihrem Konto und aktualisieren die Seite, um das komplette Album zu hören)

FRANK MARTIN: DAS MÄRCHEN VOM ASCHENBRÖDEL (LE CONTE DE CENDRILLON

Like César Franck or Leoš Janácek; Frank Martin belongs to those composers whose language went through a long period of development before maturing fully as they approached their fifties. He did not attend a music school but trained - at the same time as his classical studies – with a single master; Joseph Lauber. The latter; a prolific composer whom his pupil rightly deemed “a very good technician; but less of an artist”; imparted to him a mastery of musical writing that Frank Martin never ceased to better through his own studies of the great masters.

Although his Trois Poèmes païens (1910); the first of his works to appear in his catalogue; is still under Post-romantic influence; Frank Martin soon freed himself from it to steer towards Impressionism (Les Dithyrambes; Pavane couleur du temps) before gradually turning towards other means of expression. Around 1925 he developed a passion for rhythmic research; leading him to become a disciple of Emile Jaques-Dalcroze; and of which such works as the Trio sur des thèmes populaires irlandais (Trio based on popular Irish melodies) or Rythmes (for full orchestra) are examples. During the following decade; his interest in dodecaphony and his approach towards emancipation from tonal music can be seen in his First Piano Concerto; the Symphony and the String Trio. All of this research; all these transcended influences filtered through the prism of his exceptional personality and talent; make up the language of his mature years. This language first appears in all its fullness in the secular oratorio Le Vin herbé (1938-41) that Frank Martin himself defined as «[…] the first important work in which I spoke my own language. »

The years 1940 to 1949 witnessed the creation of numerous ballets by Swiss composers such as Jean Binet (L’Ile enchantée); Henri Gagnebin (Printemps); Hans Haug (L’Indifférent) Arthur Honegger (La Naissance des couleurs; L’Appel de la montagne); André-François Marescotti (Les Anges du Greco) and Frank Martin who wrote Das Märchen vom Aschenbrödel during the autumn of 1941; shortly after completing Le Vin Herbé. The composer had already tried his hand at ballet music with Die blaue Blume; which had won a second prize in 1935 in a competition organized by the Zurich Theatre; but which was never staged and whose orchestration was never finished.

Das Märchen vom Aschenbrödel was first performed at the Basel Municipal Theatre on 12th March 1942; conducted by Paul Sacher; together with a choreographic performance of Monteverdi’s Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda. It is based on Aschenputtel; the tale by the Grimm brothers – very similar to Charles Perrault’s Cinderella – onto which the dancer Marie-Eve Kreis built a scenario. Despite its great initial success; this remarkably innovative score was then totally and unjustly forgotten.

The work is divided into three acts and uses a small; unusual palette of instruments: a flute; an oboe; a trumpet; a trombone; two saxophones; a piano; percussion and strings. Four singers (soprano; mezzo-soprano; contralto and tenor) share the different character parts; their texts being mostly taken from Grimm’s original tale. The score shows an underestimated angle of Frank Martin’s art; a charm and sense of humour already visible in La Nique à Satan; a wonderful popular show composed in 1929; and again present in the opera Monsieur de Pourceaugnac.

The first act starts with a long sung introduction; presenting the characters and setting the action: after the death of his wife; Aschenbrödel’s father remarried; this nasty second wife and her two daughters proceed to turn the poor child’s life into absolute misery. The curtain rises on this evil household; the music portraying the opposing natures: suffering and kindness on one hand; materialism and meanness on the other. Frank Martin commented on this himself: In a most spontaneous fashion; the material element expressed itself in a style inspired by jazz music. Jazz holds an obvious esthetical value for me; it is invariably impregnated into each of us; ready to spring out at the first opportunity. But it is an art and esthetic beauty totally void of any ethical value; a purely material; soulless type of art and beauty. […] On the contrary; there is evolution in Aschenbrödel; although matter is unchanging; the spirit is by essence the source of all development. […] To represent Aschenbrödel’s humility; the oboe seemed to me the obvious choice; with its rustic yet profound sound. […] As for the Fairy; her formal yet mysterious intervention will be depicted by the flute and muted strings […]. Having outlined the heroine’s distress; the first act then hosts the intervention of the Fairy; who adorns Aschenbrödel for the ball held by the Prince; to which her step-mother refused to take her.

Act two takes place at the Royal Palace. The ball is in full swing when Aschenbrödel appears; magnificent; no one recognizing her. The Prince is hypnotized; he leads her into a fabulous waltz; suddenly interrupted by the twelve strikes of midnight and the young lady’s flight; leaving the King’s son in despair. He swears he will only marry the one whose foot will fit into the shoe left behind by the mysterious visitor.

Act three begins by a fugato – in which the four singers echo the Prince’s oath – then brings us back to the set of the first act. Aschenbrödel is dreaming about the events as the two sisters barge in; furious at having been eclipsed by her. They go as far as mutilating their foot to try to fit it into the shoe brought by the messenger; and the younger sister is about to succeed when the birds; Aschenbrödel’s friends; tell of the treachery. The Prince discovers the young girl whom the step-mother was trying to hide; takes her into a slow dance while the three vile women are punished by the birds and all the singers celebrate; as Frank Martin says; the victory of good over evil; of spirit over matter.

Jacques Tchamkerten - Head of the Library of the Geneva Music Conservatory

REVIEWS

"[..] Le compositeur en exploite toutes les ressources expressives, et son inventivité nous vaut une fin d’acte I surnaturelle, une scène de bal enamourée, un final angoissant jusqu’au triomphant happy end. A l’écoute aveugle, rien ne distingue l’Orchestre de la Haute Ecole de Musique de Genève d’un ensemble professionnel. Ils servent une équipe de chanteurs engagés, d’où émerge le soprano velouté de Clémence Tilquin, sous la direction fine et légère du chef Gabor Takacs-Nagy. Un apport significatif à la discographie de Frank Martin." - Olivier Gutierrez, avril 2013

"[..] His fairies are accompanied by music that’s just as delicate as Prokofiev’s, and I’d argue that Martin’s visceral depiction of midnight’s chimes is more terrifying, the texture abruptly thinning after the twelfth bell stroke. The vocal parts are delicious, particularly the pair of women’s voices used to portray the birds’ chorus. The closing chorus is magical. The orchestral playing is indecently accomplished, the players’ sense of shared discovery palpable. Unmissable, in other words. Track this CD down and buy multiple copies for friends and acquaintances. They’ll be grateful." - Graham Rickson, May 2013

"[..] «Le conte de Cendrillon» erzählt die bekannte Aschenputtel-Geschichte, der (deutsche) Text von Marie-Eve Kreis bleibt eng an der Grimm’schen Vorlage. Das gut einstündige Ballett wurde nun nach dem grossen Erfolg der Uraufführung seinem langen Dornröschenschlaf entrissen. Dank Genfer Interpreten: Die Musikhochschule und das Grand Théâtre brachten das Stück vor drei Jahren mit wiederum grossem Erfolg auf die Bühne, das Orchester der «Haute École de musique» der Rhonestadt unter der Leitung von Gábor Takács-Nagy ging anschliessend ins Studio und spielte es für Claves ein. Zwar kämpfen einige der vier Sänger manchmal ein bisschen mit den Tücken der deutschen Sprache, aber sonst gibt es an dieser wundervollen Aufnahme nichts auszusetzen: Sängerisch haben die Solisten ihre Partien mit ausdrucksvollem und souveränem Gesang im Griff, und das Instrumental ensemble, das insbesondere in den immer wieder mit virtuosen oder jazzigen Soli herausgefordert ist, macht beste Figur in diesem hörenswerten Martin-Ballett." - Reinmar Wagner, August 2013

"Si vous assimilez la musique de Frank Martin uniquement à l’austérité grandiose de Golgotha et de ses autres oeuvres d’inspiration religieuse, vous avez une idée limitée de la diversité de ses registres. Le compositeur genevois a cultivé tous les genres. Le moins connu est bien celui du ballet! Au beau milieu de la guerre, alors qu’il vient de terminer Le Vin herbé.[..]" - Pierre Michot, janvier 2013

"[..] L’enregistrement de la RTS a immédiatement aiguisé la curiosité puis l’intérêt du label Claves, installé à Pully et dirigé depuis peu par Patrick Peikert. «Cette redécouverte d’une partition totalement oubliée entre parfaitement dans l’esprit de notre maison», s’enthousiasme le producteur, bluffé non seulement par l’oeuvre, mais encore par l’interprétation fabuleuse des étudiants genevois dirigés par Gábor Takács-Nagy. «L’enregistrement est accessible depuis trois semaines sur plateforme électronique et suscite déjà beaucoup de réactions, jusqu’au Japon.» [..]" - Dominique Rosset, février 2013

"[..] Den Charakter der Stiefmutter und der ambitiösen Schwestern geben Saxofon und Blechbläser in jazznahem Stil wieder. Für Aschenbrödel stehen Oboe und Flöte sowie die Streicher mit noblen Klängen ein. Das Genfer Hochschulorchester bringt die unterschiedlichen Tanzweisen auf ansprechendem Niveau zum Klingen. Die vier Solisten pflegen nicht immer ein astreines Deutsch, geben aber die Charaktere der Märchenfiguren treffend wieder. Pikant, dass die böse Stiefmutter und die gute Fee von derselben Solistin gesungen werden. [..] - Mai 2013

Like César Franck or Leoš Janácek; Frank Martin belongs to those composers whose language went through a long period of development before maturing fully as they approached their fifties. He did not attend a music school but trained - at the same time as his classical studies – with a single master; Joseph Lauber. The latter; a prolific composer whom his pupil rightly deemed “a very good technician; but less of an artist”; imparted to him a mastery of musical writing that Frank Martin never ceased to better through his own studies of the great masters.

Although his Trois Poèmes païens (1910); the first of his works to appear in his catalogue; is still under Post-romantic influence; Frank Martin soon freed himself from it to steer towards Impressionism (Les Dithyrambes; Pavane couleur du temps) before gradually turning towards other means of expression. Around 1925 he developed a passion for rhythmic research; leading him to become a disciple of Emile Jaques-Dalcroze; and of which such works as the Trio sur des thèmes populaires irlandais (Trio based on popular Irish melodies) or Rythmes (for full orchestra) are examples. During the following decade; his interest in dodecaphony and his approach towards emancipation from tonal music can be seen in his First Piano Concerto; the Symphony and the String Trio. All of this research; all these transcended influences filtered through the prism of his exceptional personality and talent; make up the language of his mature years. This language first appears in all its fullness in the secular oratorio Le Vin herbé (1938-41) that Frank Martin himself defined as «[…] the first important work in which I spoke my own language. »

The years 1940 to 1949 witnessed the creation of numerous ballets by Swiss composers such as Jean Binet (L’Ile enchantée); Henri Gagnebin (Printemps); Hans Haug (L’Indifférent) Arthur Honegger (La Naissance des couleurs; L’Appel de la montagne); André-François Marescotti (Les Anges du Greco) and Frank Martin who wrote Das Märchen vom Aschenbrödel during the autumn of 1941; shortly after completing Le Vin Herbé. The composer had already tried his hand at ballet music with Die blaue Blume; which had won a second prize in 1935 in a competition organized by the Zurich Theatre; but which was never staged and whose orchestration was never finished.

Das Märchen vom Aschenbrödel was first performed at the Basel Municipal Theatre on 12th March 1942; conducted by Paul Sacher; together with a choreographic performance of Monteverdi’s Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda. It is based on Aschenputtel; the tale by the Grimm brothers – very similar to Charles Perrault’s Cinderella – onto which the dancer Marie-Eve Kreis built a scenario. Despite its great initial success; this remarkably innovative score was then totally and unjustly forgotten.

The work is divided into three acts and uses a small; unusual palette of instruments: a flute; an oboe; a trumpet; a trombone; two saxophones; a piano; percussion and strings. Four singers (soprano; mezzo-soprano; contralto and tenor) share the different character parts; their texts being mostly taken from Grimm’s original tale. The score shows an underestimated angle of Frank Martin’s art; a charm and sense of humour already visible in La Nique à Satan; a wonderful popular show composed in 1929; and again present in the opera Monsieur de Pourceaugnac.

The first act starts with a long sung introduction; presenting the characters and setting the action: after the death of his wife; Aschenbrödel’s father remarried; this nasty second wife and her two daughters proceed to turn the poor child’s life into absolute misery. The curtain rises on this evil household; the music portraying the opposing natures: suffering and kindness on one hand; materialism and meanness on the other. Frank Martin commented on this himself: In a most spontaneous fashion; the material element expressed itself in a style inspired by jazz music. Jazz holds an obvious esthetical value for me; it is invariably impregnated into each of us; ready to spring out at the first opportunity. But it is an art and esthetic beauty totally void of any ethical value; a purely material; soulless type of art and beauty. […] On the contrary; there is evolution in Aschenbrödel; although matter is unchanging; the spirit is by essence the source of all development. […] To represent Aschenbrödel’s humility; the oboe seemed to me the obvious choice; with its rustic yet profound sound. […] As for the Fairy; her formal yet mysterious intervention will be depicted by the flute and muted strings […]. Having outlined the heroine’s distress; the first act then hosts the intervention of the Fairy; who adorns Aschenbrödel for the ball held by the Prince; to which her step-mother refused to take her.

Act two takes place at the Royal Palace. The ball is in full swing when Aschenbrödel appears; magnificent; no one recognizing her. The Prince is hypnotized; he leads her into a fabulous waltz; suddenly interrupted by the twelve strikes of midnight and the young lady’s flight; leaving the King’s son in despair. He swears he will only marry the one whose foot will fit into the shoe left behind by the mysterious visitor.

Act three begins by a fugato – in which the four singers echo the Prince’s oath – then brings us back to the set of the first act. Aschenbrödel is dreaming about the events as the two sisters barge in; furious at having been eclipsed by her. They go as far as mutilating their foot to try to fit it into the shoe brought by the messenger; and the younger sister is about to succeed when the birds; Aschenbrödel’s friends; tell of the treachery. The Prince discovers the young girl whom the step-mother was trying to hide; takes her into a slow dance while the three vile women are punished by the birds and all the singers celebrate; as Frank Martin says; the victory of good over evil; of spirit over matter.

Jacques Tchamkerten - Head of the Library of the Geneva Music Conservatory

REVIEWS

"[..] Le compositeur en exploite toutes les ressources expressives, et son inventivité nous vaut une fin d’acte I surnaturelle, une scène de bal enamourée, un final angoissant jusqu’au triomphant happy end. A l’écoute aveugle, rien ne distingue l’Orchestre de la Haute Ecole de Musique de Genève d’un ensemble professionnel. Ils servent une équipe de chanteurs engagés, d’où émerge le soprano velouté de Clémence Tilquin, sous la direction fine et légère du chef Gabor Takacs-Nagy. Un apport significatif à la discographie de Frank Martin." - Olivier Gutierrez, avril 2013

"[..] His fairies are accompanied by music that’s just as delicate as Prokofiev’s, and I’d argue that Martin’s visceral depiction of midnight’s chimes is more terrifying, the texture abruptly thinning after the twelfth bell stroke. The vocal parts are delicious, particularly the pair of women’s voices used to portray the birds’ chorus. The closing chorus is magical. The orchestral playing is indecently accomplished, the players’ sense of shared discovery palpable. Unmissable, in other words. Track this CD down and buy multiple copies for friends and acquaintances. They’ll be grateful." - Graham Rickson, May 2013

"[..] «Le conte de Cendrillon» erzählt die bekannte Aschenputtel-Geschichte, der (deutsche) Text von Marie-Eve Kreis bleibt eng an der Grimm’schen Vorlage. Das gut einstündige Ballett wurde nun nach dem grossen Erfolg der Uraufführung seinem langen Dornröschenschlaf entrissen. Dank Genfer Interpreten: Die Musikhochschule und das Grand Théâtre brachten das Stück vor drei Jahren mit wiederum grossem Erfolg auf die Bühne, das Orchester der «Haute École de musique» der Rhonestadt unter der Leitung von Gábor Takács-Nagy ging anschliessend ins Studio und spielte es für Claves ein. Zwar kämpfen einige der vier Sänger manchmal ein bisschen mit den Tücken der deutschen Sprache, aber sonst gibt es an dieser wundervollen Aufnahme nichts auszusetzen: Sängerisch haben die Solisten ihre Partien mit ausdrucksvollem und souveränem Gesang im Griff, und das Instrumental ensemble, das insbesondere in den immer wieder mit virtuosen oder jazzigen Soli herausgefordert ist, macht beste Figur in diesem hörenswerten Martin-Ballett." - Reinmar Wagner, August 2013

"Si vous assimilez la musique de Frank Martin uniquement à l’austérité grandiose de Golgotha et de ses autres oeuvres d’inspiration religieuse, vous avez une idée limitée de la diversité de ses registres. Le compositeur genevois a cultivé tous les genres. Le moins connu est bien celui du ballet! Au beau milieu de la guerre, alors qu’il vient de terminer Le Vin herbé.[..]" - Pierre Michot, janvier 2013

"[..] L’enregistrement de la RTS a immédiatement aiguisé la curiosité puis l’intérêt du label Claves, installé à Pully et dirigé depuis peu par Patrick Peikert. «Cette redécouverte d’une partition totalement oubliée entre parfaitement dans l’esprit de notre maison», s’enthousiasme le producteur, bluffé non seulement par l’oeuvre, mais encore par l’interprétation fabuleuse des étudiants genevois dirigés par Gábor Takács-Nagy. «L’enregistrement est accessible depuis trois semaines sur plateforme électronique et suscite déjà beaucoup de réactions, jusqu’au Japon.» [..]" - Dominique Rosset, février 2013

"[..] Den Charakter der Stiefmutter und der ambitiösen Schwestern geben Saxofon und Blechbläser in jazznahem Stil wieder. Für Aschenbrödel stehen Oboe und Flöte sowie die Streicher mit noblen Klängen ein. Das Genfer Hochschulorchester bringt die unterschiedlichen Tanzweisen auf ansprechendem Niveau zum Klingen. Die vier Solisten pflegen nicht immer ein astreines Deutsch, geben aber die Charaktere der Märchenfiguren treffend wieder. Pikant, dass die böse Stiefmutter und die gute Fee von derselben Solistin gesungen werden. [..] - Mai 2013

Return to the album | Read the booklet | Composer(s): Frank Martin | Main Artist: Gábor Takács-Nagy