(2021) Bach: h-moll Messe, Gli Angeli Genève, Stephan Macleod

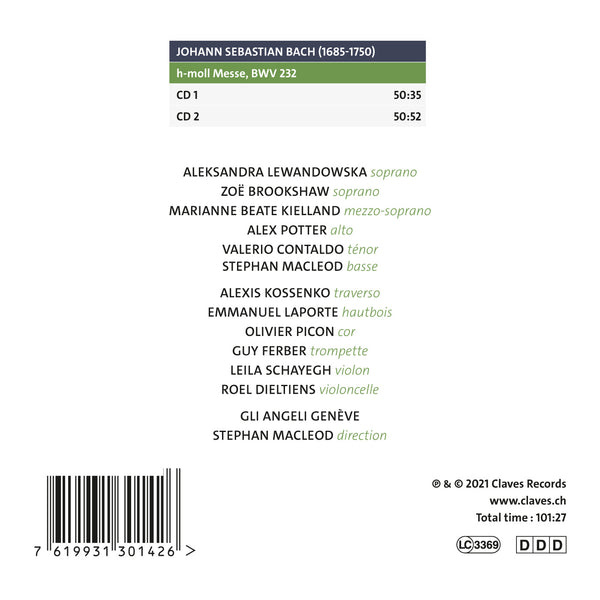

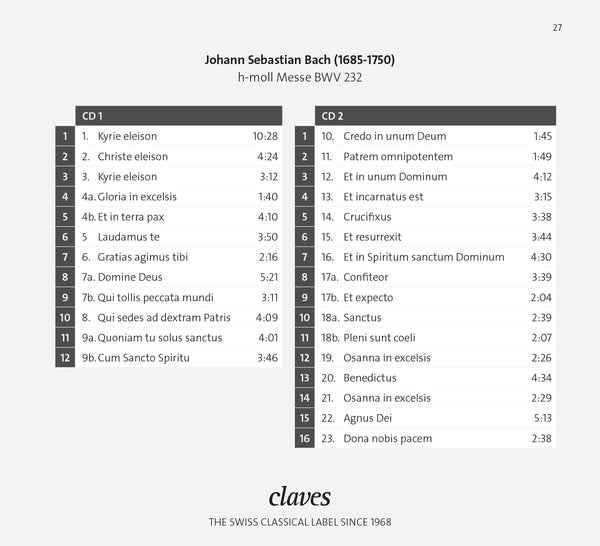

Kategorie(n): Alte Musik Operngesang Repertoire

Instrument(e): Violoncello Flöte Cor Oboe Trompete Geige

Gesangsstimme(n): Alt Mezzo-soprano Soprano Tenor

Hauptkomponist: Johann Sebastian Bach

Ensemble: Gli Angeli Genève

Dirigent: Stephan MacLeod

CD-Set: 2

Katalog Nr.:

CD 3014/15

Freigabe: 26.03.2021

EAN/UPC: 7619931301426

Dieses Album ist jetzt neu aufgelegt worden. Bestellen Sie es jetzt zum Sonderpreis vor.

CHF 24.00

Dieses Album ist noch nicht veröffentlicht worden. Bestellen Sie es jetzt vor.

CHF 24.00

CHF 24.00

Inklusive MwSt. für die Schweiz und die EU

Kostenloser Versand

Inklusive MwSt. für die Schweiz und die EU

Kostenloser Versand

Dieses Album ist jetzt neu aufgelegt worden. Bestellen Sie es jetzt zum Sonderpreis vor.

CHF 24.00

This album has not been released yet.

Pre-order it at a special price now.

CHF 24.00

CHF 24.00

SPOTIFY

(Verbinden Sie sich mit Ihrem Konto und aktualisieren die Seite, um das komplette Album zu hören)

BACH: H-MOLL MESSE, GLI ANGELI GENÈVE, STEPHAN MACLEOD

Bach – Die h-Moll-Messe

Die Messe in h-Moll nimmt in J. S. Bachs Werk einen ganz besonderen Platz ein: ein Werk von großer Bedeutung, ein opus ultimum, das nicht als solches komponiert wurde, sondern das Ergebnis einer Zusammenstellung von Stücken ist, die zu unterschiedlichen Zeiten und für unterschiedliche Anlässe geschrieben wurden. Bach arbeitete in den Jahren 1748–1749 daran, bis sein Sehvermögen, das sich allmählich verschlechtert hatte, vollständig verloren ging – ein Empfehlungsschreiben für seinen Sohn Johann Christoph Friedrich vom 17. Dezember 1749 wurde von Anna Magdalena verfasst, die seine Unterschrift imitierte. In Leipzig ging das Gerücht um, dass sich der Gesundheitszustand des Kantors so sehr verschlechtert hatte, dass der Stadtrat auf Anordnung des allmächtigen sächsischen Ministers am 8. Juni 1749 einen Kapellmeister aus Dresden vorspielen ließ, der ihm für „die künftige Stelle des Thomaskantors im Falle des Ablebens des Director musices Sebastian Bach“ empfohlen worden war. Zu diesem Zeitpunkt arbeitete Bach an seiner Messe, die größer war als alles, was jemals zuvor erdacht worden war[1]. Sein eher blasser Nachfolger musste ein weiteres Jahr warten, um ihn zu ersetzen, da Bach am 28. Juli 1750 starb.

***

Eine monumentale Messe

Die Idee, Stücke zusammenzustellen, die im Wesentlichen aus dem riesigen Korpus der Kantaten stammen, war nicht ungewöhnlich; ein ähnlicher Ansatz wurde von mehreren seiner Zeitgenossen, wie Händel, verfolgt, und Bach selbst hatte dies für die kurzen Messen getan, die er in den späten 1730er Jahren komponierte[2]. Diese wurden Parodien genannt. Der Wechsel vom deutschen Text der Kantaten zum lateinischen Text der Messen bedeutete eine Anpassung der Gesangslinien mit Hinzufügungen und Streichungen, polyphonen und harmonischen Anreicherungen und Änderungen in der Instrumentierung. Sein ganzes Leben lang hörte Bach nie auf, seine Werke zu überarbeiten, um sie zu verbessern.

Bach stellte sich die Produktion einer monumentalen Messe vor, die als musikalisches Testament für ihn angesehen werden kann, und begann damit, das Repertoire seiner eigenen Musik zu erforschen, während er verschiedene Messen anderer Komponisten studierte, die ihm zur Verfügung standen (und zu den Partituren, die er studierte, gehörte Pergolesis Stabat mater, das er selbst bearbeitet hatte). Er entschied sich vor allem für eine Messe (Missa in lutherischer Sprache), die 1733 nach dem Tod von August dem Starken am 1. Februar komponiert wurde, dem Herrscher des lutherischen Sachsens, von dem Leipzig und das katholische Polen abhingen. Sie bestand, wie es bei den lutherischen Messen der Fall war, aus dem Kyrie und dem Gloria, deren Musik größtenteils original war (nur vier der neun Stücke im Gloria stammen aus früheren Kompositionen). Bach wollte jedoch eine Messe mit den verschiedenen Teilen des katholischen Ordinarius komponieren, mit Credo, Sanctus, Benedictus und Agnus Dei. Angesichts der Größe der beiden Sätze der Missa, von denen jeder so beeindruckend ist wie der andere, war Bach gezwungen, ein umfangreiches Credo zu schreiben.

Das Kyrie von 1733 war als Tribut an den Verstorbenen gedacht, während das Gloria seinen Nachfolger feierte, der kein anderer als sein eigener Sohn war (sie waren beide große Förderer der Künste). Es ist nicht bekannt, ob das Werk in Leipzig aufgeführt wurde oder ob es in der sächsischen Hauptstadt entstand. Anscheinend nicht, denn es gibt kein Dokument, das dies erwähnt. Auf jeden Fall wurde die Partitur Ende Juli zusammen mit den Einzelstimmen, die mehrere Mitglieder der Familie Bach in aller Eile kopiert hatten, an den neuen Herrscher geschickt. Dem Schreiben lag eine Bitte bei, in der der Kantor sich über die „Beleidigungen“ in Leipzig beschwerte und hoffte, seine Position durch eine Anstellung als Hofkomponist zu stärken, eine reine Ehrenposition, die keinerlei Verpflichtungen mit sich brachte. Einen Monat zuvor hatte er seinen ältesten Sohn Wilhelm Friedemann zum Organisten der Sophienkirche in Dresden ernannt. Friedrich August II. war jedoch in den Streit um die polnische Thronfolge verwickelt, der gerade ausgetragen wurde. Bachs Bitte, die er drei Jahre später wiederholte, wurde erhört, als er mit dem neuen Rektor der Thomaskirche und dem Leipziger Rat kämpfte, denen der Herrscher schließlich befahl, Bach die Ausübung seiner musikalischen Autorität zu gestatten.

>> Lesen Sie mehr in der Broschüre <<

__________

[1] Die h-Moll-Messe dauert etwa eine Stunde und vierzig Minuten, was sie zu einem sehr ungewöhnlichen Werk macht, das nicht in eine religiöse Zeremonie integriert werden konnte. Zelenkas Missa votiva aus dem Jahr 1739, die in ihrer Struktur der von Bach sehr ähnelt, dauert etwas mehr als eine Stunde (Zelenka, dessen Musik Bach kannte, war Komponist am Dresdner Hof).

[2] Neben der hier besprochenen Missa von 1733 komponierte Bach vier lutherische Messen (die nur aus einem Kyrie und einem Gloria bestehen): BWV 233 bis 236

***

Zehn Sänger für eine h-Moll-Messe

Seit Jahren beschäftigen sich Musikwissenschaftler und Musiker mit der Frage, welche Vokalkräfte Johann Sebastian Bach für seine Kantaten und Passionen zur Verfügung standen. Mit Hilfe gelegentlich neu entdeckter Quellen und eingehender Studien konnten wir aufschlussreiche Antworten auf ein Problem finden, das für die Interpretation seiner Musik von wesentlicher Bedeutung ist. In diesem Zusammenhang scheint es mir wichtig klarzustellen, dass wir uns der h-Moll-Messe nicht mit einem Ensemble von zehn Sängern genähert haben, um der Authentizität willen, und auch nicht, um unseren Standpunkt zu vertreten, wie die Dinge getan werden sollten oder nicht. Bei der Suche nach Authentizität vergessen wir manchmal, dass Musiker damals wie heute immer pragmatisch waren und sich immer an unterschiedliche Einschränkungen anpassen konnten: Budgets, Stimmgabeln, Zahlen, verfügbare Instrumente usw. Die historische Realität allein ist daher nicht immer ein so relevanter Begriff, und wir haben nicht die Ambition, an den oft faszinierenden Debatten teilzunehmen, die solche Forschungen auslösen. Wenn unsere Arbeit dazu beitragen kann, bestimmte Standpunkte zu entwickeln, anderen Relevanz zu verleihen, Menschen zum Handeln zu bewegen und den Fortschritt bestimmter Ideen und Überzeugungen zu fördern, umso besser, aber unsere eigenen Beweggründe sind andere.

Seit seiner Gründung im Jahr 2005 hat sich Gli Angeli Genève Bachs Musik mit zwei Sängern pro Part angenähert: d. h. acht Sänger für die meisten Kantaten, acht Sänger für die Johannes-Passion, sechzehn für die Matthäus-Passion und ihre beiden Chöre ( wie unsere im April 2020 bei Claves veröffentlichte Aufnahme zeigt), zehn für das Magnificat (wo die Chöre fünfstimmig sind) oder für die Messe in h-Moll (wo eine Besetzung von zwölf Sängern wegen des sechsstimmigen Sanctus logischer wäre). Zwei Sänger pro Stimme in den Chören ist die Anzahl der Sänger in Carl Philip Emmanuel Bachs Chor für viele seiner großen Oratorien und die Anzahl der Sänger in Joseph Haydns Chor für viele seiner Messen. Aber auch hier sind diese historischen Gegebenheiten nicht die Grundlage unseres Ansatzes und unserer Wahl. Ein Musiker mag in seinem Bedürfnis, seine ästhetischen Entscheidungen durch sein Geschichtswissen zu legitimieren, gerechtfertigt sein, aber wenn die Suche nach Authentizität zur einzigen treibenden Kraft hinter seiner Arbeit wird, kann er in die Irre gehen. Es ist daher ein weiterer Faktor, der uns anzieht und motiviert.

Zu Bachs Zeiten sangen die Sänger in Leipzig, unabhängig von ihrer genauen Anzahl, vor den Instrumentalisten und nicht hinter ihnen. Religiöse Musik existierte gemäß dem Verb, das sie verherrlichte, da Instrumentalisten und Sänger zu dieser Zeit dieselbe Sprache und Kultur teilten. Indem wir die Sänger heute vor die Instrumente stellen, wie wir es bei Gli Angeli Genève tun, geben wir dem Wort seinen rechtmäßigen Platz zurück: den ersten, den, der diese Vokalmusik begründet und inspiriert. Und wenn der Chor vor den Instrumenten singt, braucht er nicht viele Mitglieder zu haben, da das Gleichgewicht zwischen Stimme und Orchester viel einfacher zu erreichen ist. Das ist der Unterschied zwischen der klassischen Position eines großen Chors hinter den Instrumenten, der Anordnung, mit der meine Generation aufgewachsen ist, zugehört, gespielt, gesungen und diese Musik gelernt hat, und die auch heute noch in Kirchen und Konzertsälen am häufigsten zu finden ist.

Schließlich können zwei Stimmen, die denselben Part singen, nicht zu einem einzigen Klang oder einer einzigen Klangfarbe verschmelzen, wie es bereits bei drei Stimmen möglich ist. Dies ist weit entfernt von der Klangfülle des großen romantischen Chors. Andererseits sind die Stimmen eines solchen Ensembles individueller, sowohl im Klang als auch in der Interpretation. Im Fall von Gli Angeli Genève sind es die Stimmen einer Gruppe von Freunden, die beschlossen haben, gemeinsam zu singen und ihre jeweiligen Klangfarben zum Ausdruck ihres Glücks und ihrer Freude zu bringen, indem sie die Musik für sich selbst sprechen lassen.

***

Gli Angeli Geneva - www.gliangeligeneve.com

Gli Angeli Genève wurde 2005 von Stephan MacLeod gegründet. Das Ensemble besteht aus Musikern, die sich auf Barockmusik spezialisiert haben, aber nicht nur in diesem Bereich tätig sind: Sie spielen nicht nur Alte Musik. Ihre Vielseitigkeit garantiert die Vitalität ihres Enthusiasmus. Sie ist auch die treibende Kraft hinter ihrer Neugier.

Seit Beginn eines musikalischen Abenteuers, das sich mehrere Jahre lang ausschließlich auf Live-Aufführungen der vollständigen Bach-Kantaten in Genf mit drei Konzerten pro Saison konzentrierte, ist Gli Angeli Genève der Schauplatz für Begegnungen zwischen einigen der berühmtesten Sänger und Instrumentalisten der internationalen Barockszene und jungen Absolventen der Musikhochschulen von Basel, Lyon, Lausanne und Genf.

Seit der Veröffentlichung seiner ersten beiden CDs in den Jahren 2009 und 2010, die zahlreiche Kritikerpreise gewannen, ist das Ensemble international bekannt und gibt nun sieben oder acht Konzerte pro Saison in Genf, zum einen im Rahmen seiner Reihe „Complete Bach Cantatas“, einer Reihe von jährlichen Konzerten in der Victoria Hall, zum anderen seit September 2017 in einer neuen vollständigen Reihe, die Haydns Symphonien gewidmet ist. Das Ensemble ist in der Schweiz und im Ausland gleichermaßen gefragt für Aufführungen nicht nur von Bach, sondern auch von Tallis, Josquin, Schein, Schütz, Johann Christoph Bach, Weckmann, Buxtehude, Rosenmüller, Haydn, Mozart und anderen. In den letzten Spielzeiten war Gli Angeli Genève beim Utrecht Festival und den Thüringer Bachwochen, residiert und trat auch in Basel, Zürich, Luzern, Barcelona, Nürnberg, Bremen, Stuttgart, Brüssel, Mailand, Breslau, Paris, Ottawa, Vancouver, Amsterdam und Den Haag auf. Gli Angeli Genève ist regelmäßiger Gast beim Festival de Saintes, beim Utrecht Festival, beim Musikfest Bremen oder beim Bach Festival Vancouver. Das Ensemble gab 2017 sein Debüt am Grand Théâtre in Genf und 2019 am KKL in Luzern.

Die vorletzte Aufnahme von Gli Angeli Genève für Claves, Sakrale Musik des 17. Jahrhunderts in Breslau, gewann 2019 den ICMA-Preis für die beste Vokalaufnahme mit Barockmusik des Jahres, und seine neueste Aufnahme, Die Matthäus-Passion von Johann Sebastian Bach, wird sowohl vom Publikum als auch von der Kritik in der Schweiz und weltweit begeistert aufgenommen.

Übersetzt aus dem Englischen mit www.DeepL.com/Translator

REVIEWS

“This studio recording of Bach’s greatest work, though one he only ever heard in his imagination, is notable for its transparent textures due to MacLeod’s decision to limit his singers to ten – a decision taken when Gli Angeli Genève was founded in 2005. In his booklet note MacLeod persuasively argues that such restrictions are not undertaken for strict historical authenticity – other reasons pertain, including placing all the singers in front of the instrumentalists, as would have occurred in the Thomaskirche in Bach’s day. On the recording this has the benefit of foregrounding the text and thereby to an extent solving many of the balance issues that occur in a conventional set-up. [..]” -Philip Reed, August 2021

« [..] Ansonsten punktet sie mit ihrer technischen Perfektion und ihrer musikalischen Homogenität. MacLeod geht es mehr um analytische Klarheit als um spirituelle Überhöhung; dementsprechend direkt und zügig ist sein Ansatz. Von den durchweg exzellenten Instrumentalsoli ist Leila Schayeghs Geigenspiel im „Laudamus te“ besonders hervorzuheben. » - Matthias Hengelbrock, September 2021

« [..] Dans cet opus, Stephan MacLeod et son ensemble Gli Angeli Genève abordent la messe avec dix chanteurs au total. Bach faisait pareil pour ses cantates de sorte à favoriser la parole à l'orchestre. Les voix s'épanouissent et sont soutenues admirablement par l'orchestre. [..] » - Septembre 2021

“Gli Angeli Genève perform the Mass in B minor with 10 singers (six concertists and four ripienists) and an orchestra of 27 players, each section led by outstanding musicians. Director (and bass) Stephan MacLeod enthuses that two singers on each line in the choruses, placed in front of the orchestra instead of behind it, is ‘more individualised, both in sound and interpretation … their respective timbres express their happiness and pleasure in letting music speak for itself’. [..] Overall, Gli Angeli Genève’s performance is characterised by swift momentum, crisp articulation and benevolent attention to detail.” - David Vickers, July 2021

« [..] Nach der famosen Matthäus-Passion vor einem Jahr nun eine h-Moll-Messe vom selben Kaliber: Ein Plädoyer für die schlanke Vokalbesetzung, ohne ideologische Verengung oder argumentativen Schaum vor dem Mund. Im Gegenteil: Ein funkensprühendes Erlebnis hochstehender Musikalität und stupenden Vermögens. Stephan MacLeod und sein Ensemble Gli Angeli Genève treten seit längerer Zeit vernehmlich als – vielleicht weithin nicht genug geschätzte – Bach-Kraft von Rang hervor. Dazu ist es ein wunderbares künstlerisches Lebenszeichen aus dem düsteren Corona-Herbst 2020. » - Dr. Matthias Lange, Mai 2021

« Interview. Il y a un an, Stephan MacLeod émouvait déjà dans Bach. La Passion selon saint Matthieu de l’ensemble Gli Angeli Genève faisait exploser les compteurs des téléchargements de la maison Claves. Une période de confinement en chasse une autre: il faut aujourd’hui encore se contenter de captations ou d’enregistrements en ce temps de Pâques. Mais Bach est toujours là qui nous tient la main, nous console et nous rassure de la beauté du monde. Interview du chef, qui offre ce printemps la Messe en si mineur. [..] » - Elisabeth Hass, avril 2021

“[..] Emotions are relegated to the background, instead much emphasis is placed on an objective and therefore very academic interpretation, which at best can please those who like an intellectual and professorial Bach.” - Alain Steffen, mars 2021

“[..] This is a creation of a very high level of interpretation, carefully thought out and carefully realised in the context of historical performance practices and the use of appropriate instrumentation, as evidenced by the very person of the ensemble's conductor and bass player, Stephen MacLeod, an artist who researches the lesser-known Baroque repertoire. [..] If I had to characterise this recording in a few words or one sentence, I would use the following words: beautiful, honest and modest. There are many fine recordings of this repertoire, more or less famous, spectacular and exciting, but by communing with the creation of the singers and the ensemble of Gli Angeli Genève under the direction of Stephan MacLeod, I was able not only to relax but also to comfort my mind, my heart and my soul. [..]” - Paweł Chmielowski, August 2021

“[..] The smaller forces in this new recording give a lovely transparency to the overall sound, beneficial in such compositional complexity, and an intimacy missing in recordings using greater numbers. The string players use period instruments, adding to the clarity of texture. Ensemble work throughout is exceptional. The booklet lists the choir and orchestra on the front and photos of the performers are included. The comprehensive introduction is in three languages, but the Latin text is only translated into French. [..]” - Patrice Connolly, April 2022

« [..] Aber gerade deswegen ruft es Begeisterung hervor, wenn es einem erfahrenen Interpreten wie Stephan MacLeod gelingt, mit höchst sorgfältig ausgewählten Musikerinnen und Musikern ein Ensemble zu formieren, das den „Beinahe-Normalfall“ einer entsprechend routinierten Darbietung nochmals deutlich überbietet. MacLeod selbst leuchtet voran in der fordernden Doppelaufgabe des Vokalisten und Ensembleleiters. Zur vokalen Leistung gehört nicht zuletzt auch die brillante Bewältigung der beiden in der Tessitura so verschiedenen Bassarien. Zu ihm gesellen sich hervorragende Sängerinnen und Sänger, die gerade auch in der heiklen Zwei-pro-Stimme-Besetzung der Chorsätze eine erstaunliche Homogenität zu erzeugen verstehen. Gemeinsam mit den gleichermaßen brillanten Instrumentalistinnen und Instrumentalisten bringen sie es zu einer geschmeidigen Eleganz und filigranen Transparenz des Klanges, die ihresgleichen sucht. [..] » - Michael Wersin, Mai 2021

« Avec la Messe en si, la formation poursuit avec pertinence son exploration de Bach en s’attaquant à un monument. [..] » - Rocco Zacheo, avril 2021

« [..] Es gibt unendlich viele Aufnahmen der h-Moll-Messe. Eine neue lässt jetzt aufhorchen: Das Ensemble Gli Angeli Genève unter Leitung des mitsingenden Bassisten Stephan McLeod hat eine wirklich überzeugende und berückende Einspielung von Bachs Opus ultimum vorgelegt. [..] Diese CD sei allen, die Bach lieben, dringlichst empfohlen, egal wie viele Aufnahmen des exzeptionellen Werkes bereits im Regal stehen – und Erstlingen in Sachen h-Moll-Messe sowieso. Und da es ein Werk für alle (Kirchenjahres-)Zeiten ist, eignet es sich auch trefflich dafür, unter dem Christbaum zu liegen. » - Reinhard Mawick, November 2022

(2021) Bach: h-moll Messe, Gli Angeli Genève, Stephan Macleod - CD 3014/15

Bach – Die h-Moll-Messe

Die Messe in h-Moll nimmt in J. S. Bachs Werk einen ganz besonderen Platz ein: ein Werk von großer Bedeutung, ein opus ultimum, das nicht als solches komponiert wurde, sondern das Ergebnis einer Zusammenstellung von Stücken ist, die zu unterschiedlichen Zeiten und für unterschiedliche Anlässe geschrieben wurden. Bach arbeitete in den Jahren 1748–1749 daran, bis sein Sehvermögen, das sich allmählich verschlechtert hatte, vollständig verloren ging – ein Empfehlungsschreiben für seinen Sohn Johann Christoph Friedrich vom 17. Dezember 1749 wurde von Anna Magdalena verfasst, die seine Unterschrift imitierte. In Leipzig ging das Gerücht um, dass sich der Gesundheitszustand des Kantors so sehr verschlechtert hatte, dass der Stadtrat auf Anordnung des allmächtigen sächsischen Ministers am 8. Juni 1749 einen Kapellmeister aus Dresden vorspielen ließ, der ihm für „die künftige Stelle des Thomaskantors im Falle des Ablebens des Director musices Sebastian Bach“ empfohlen worden war. Zu diesem Zeitpunkt arbeitete Bach an seiner Messe, die größer war als alles, was jemals zuvor erdacht worden war[1]. Sein eher blasser Nachfolger musste ein weiteres Jahr warten, um ihn zu ersetzen, da Bach am 28. Juli 1750 starb.

***

Eine monumentale Messe

Die Idee, Stücke zusammenzustellen, die im Wesentlichen aus dem riesigen Korpus der Kantaten stammen, war nicht ungewöhnlich; ein ähnlicher Ansatz wurde von mehreren seiner Zeitgenossen, wie Händel, verfolgt, und Bach selbst hatte dies für die kurzen Messen getan, die er in den späten 1730er Jahren komponierte[2]. Diese wurden Parodien genannt. Der Wechsel vom deutschen Text der Kantaten zum lateinischen Text der Messen bedeutete eine Anpassung der Gesangslinien mit Hinzufügungen und Streichungen, polyphonen und harmonischen Anreicherungen und Änderungen in der Instrumentierung. Sein ganzes Leben lang hörte Bach nie auf, seine Werke zu überarbeiten, um sie zu verbessern.

Bach stellte sich die Produktion einer monumentalen Messe vor, die als musikalisches Testament für ihn angesehen werden kann, und begann damit, das Repertoire seiner eigenen Musik zu erforschen, während er verschiedene Messen anderer Komponisten studierte, die ihm zur Verfügung standen (und zu den Partituren, die er studierte, gehörte Pergolesis Stabat mater, das er selbst bearbeitet hatte). Er entschied sich vor allem für eine Messe (Missa in lutherischer Sprache), die 1733 nach dem Tod von August dem Starken am 1. Februar komponiert wurde, dem Herrscher des lutherischen Sachsens, von dem Leipzig und das katholische Polen abhingen. Sie bestand, wie es bei den lutherischen Messen der Fall war, aus dem Kyrie und dem Gloria, deren Musik größtenteils original war (nur vier der neun Stücke im Gloria stammen aus früheren Kompositionen). Bach wollte jedoch eine Messe mit den verschiedenen Teilen des katholischen Ordinarius komponieren, mit Credo, Sanctus, Benedictus und Agnus Dei. Angesichts der Größe der beiden Sätze der Missa, von denen jeder so beeindruckend ist wie der andere, war Bach gezwungen, ein umfangreiches Credo zu schreiben.

Das Kyrie von 1733 war als Tribut an den Verstorbenen gedacht, während das Gloria seinen Nachfolger feierte, der kein anderer als sein eigener Sohn war (sie waren beide große Förderer der Künste). Es ist nicht bekannt, ob das Werk in Leipzig aufgeführt wurde oder ob es in der sächsischen Hauptstadt entstand. Anscheinend nicht, denn es gibt kein Dokument, das dies erwähnt. Auf jeden Fall wurde die Partitur Ende Juli zusammen mit den Einzelstimmen, die mehrere Mitglieder der Familie Bach in aller Eile kopiert hatten, an den neuen Herrscher geschickt. Dem Schreiben lag eine Bitte bei, in der der Kantor sich über die „Beleidigungen“ in Leipzig beschwerte und hoffte, seine Position durch eine Anstellung als Hofkomponist zu stärken, eine reine Ehrenposition, die keinerlei Verpflichtungen mit sich brachte. Einen Monat zuvor hatte er seinen ältesten Sohn Wilhelm Friedemann zum Organisten der Sophienkirche in Dresden ernannt. Friedrich August II. war jedoch in den Streit um die polnische Thronfolge verwickelt, der gerade ausgetragen wurde. Bachs Bitte, die er drei Jahre später wiederholte, wurde erhört, als er mit dem neuen Rektor der Thomaskirche und dem Leipziger Rat kämpfte, denen der Herrscher schließlich befahl, Bach die Ausübung seiner musikalischen Autorität zu gestatten.

>> Lesen Sie mehr in der Broschüre <<

__________

[1] Die h-Moll-Messe dauert etwa eine Stunde und vierzig Minuten, was sie zu einem sehr ungewöhnlichen Werk macht, das nicht in eine religiöse Zeremonie integriert werden konnte. Zelenkas Missa votiva aus dem Jahr 1739, die in ihrer Struktur der von Bach sehr ähnelt, dauert etwas mehr als eine Stunde (Zelenka, dessen Musik Bach kannte, war Komponist am Dresdner Hof).

[2] Neben der hier besprochenen Missa von 1733 komponierte Bach vier lutherische Messen (die nur aus einem Kyrie und einem Gloria bestehen): BWV 233 bis 236

***

Zehn Sänger für eine h-Moll-Messe

Seit Jahren beschäftigen sich Musikwissenschaftler und Musiker mit der Frage, welche Vokalkräfte Johann Sebastian Bach für seine Kantaten und Passionen zur Verfügung standen. Mit Hilfe gelegentlich neu entdeckter Quellen und eingehender Studien konnten wir aufschlussreiche Antworten auf ein Problem finden, das für die Interpretation seiner Musik von wesentlicher Bedeutung ist. In diesem Zusammenhang scheint es mir wichtig klarzustellen, dass wir uns der h-Moll-Messe nicht mit einem Ensemble von zehn Sängern genähert haben, um der Authentizität willen, und auch nicht, um unseren Standpunkt zu vertreten, wie die Dinge getan werden sollten oder nicht. Bei der Suche nach Authentizität vergessen wir manchmal, dass Musiker damals wie heute immer pragmatisch waren und sich immer an unterschiedliche Einschränkungen anpassen konnten: Budgets, Stimmgabeln, Zahlen, verfügbare Instrumente usw. Die historische Realität allein ist daher nicht immer ein so relevanter Begriff, und wir haben nicht die Ambition, an den oft faszinierenden Debatten teilzunehmen, die solche Forschungen auslösen. Wenn unsere Arbeit dazu beitragen kann, bestimmte Standpunkte zu entwickeln, anderen Relevanz zu verleihen, Menschen zum Handeln zu bewegen und den Fortschritt bestimmter Ideen und Überzeugungen zu fördern, umso besser, aber unsere eigenen Beweggründe sind andere.

Seit seiner Gründung im Jahr 2005 hat sich Gli Angeli Genève Bachs Musik mit zwei Sängern pro Part angenähert: d. h. acht Sänger für die meisten Kantaten, acht Sänger für die Johannes-Passion, sechzehn für die Matthäus-Passion und ihre beiden Chöre ( wie unsere im April 2020 bei Claves veröffentlichte Aufnahme zeigt), zehn für das Magnificat (wo die Chöre fünfstimmig sind) oder für die Messe in h-Moll (wo eine Besetzung von zwölf Sängern wegen des sechsstimmigen Sanctus logischer wäre). Zwei Sänger pro Stimme in den Chören ist die Anzahl der Sänger in Carl Philip Emmanuel Bachs Chor für viele seiner großen Oratorien und die Anzahl der Sänger in Joseph Haydns Chor für viele seiner Messen. Aber auch hier sind diese historischen Gegebenheiten nicht die Grundlage unseres Ansatzes und unserer Wahl. Ein Musiker mag in seinem Bedürfnis, seine ästhetischen Entscheidungen durch sein Geschichtswissen zu legitimieren, gerechtfertigt sein, aber wenn die Suche nach Authentizität zur einzigen treibenden Kraft hinter seiner Arbeit wird, kann er in die Irre gehen. Es ist daher ein weiterer Faktor, der uns anzieht und motiviert.

Zu Bachs Zeiten sangen die Sänger in Leipzig, unabhängig von ihrer genauen Anzahl, vor den Instrumentalisten und nicht hinter ihnen. Religiöse Musik existierte gemäß dem Verb, das sie verherrlichte, da Instrumentalisten und Sänger zu dieser Zeit dieselbe Sprache und Kultur teilten. Indem wir die Sänger heute vor die Instrumente stellen, wie wir es bei Gli Angeli Genève tun, geben wir dem Wort seinen rechtmäßigen Platz zurück: den ersten, den, der diese Vokalmusik begründet und inspiriert. Und wenn der Chor vor den Instrumenten singt, braucht er nicht viele Mitglieder zu haben, da das Gleichgewicht zwischen Stimme und Orchester viel einfacher zu erreichen ist. Das ist der Unterschied zwischen der klassischen Position eines großen Chors hinter den Instrumenten, der Anordnung, mit der meine Generation aufgewachsen ist, zugehört, gespielt, gesungen und diese Musik gelernt hat, und die auch heute noch in Kirchen und Konzertsälen am häufigsten zu finden ist.

Schließlich können zwei Stimmen, die denselben Part singen, nicht zu einem einzigen Klang oder einer einzigen Klangfarbe verschmelzen, wie es bereits bei drei Stimmen möglich ist. Dies ist weit entfernt von der Klangfülle des großen romantischen Chors. Andererseits sind die Stimmen eines solchen Ensembles individueller, sowohl im Klang als auch in der Interpretation. Im Fall von Gli Angeli Genève sind es die Stimmen einer Gruppe von Freunden, die beschlossen haben, gemeinsam zu singen und ihre jeweiligen Klangfarben zum Ausdruck ihres Glücks und ihrer Freude zu bringen, indem sie die Musik für sich selbst sprechen lassen.

***

Gli Angeli Geneva - www.gliangeligeneve.com

Gli Angeli Genève wurde 2005 von Stephan MacLeod gegründet. Das Ensemble besteht aus Musikern, die sich auf Barockmusik spezialisiert haben, aber nicht nur in diesem Bereich tätig sind: Sie spielen nicht nur Alte Musik. Ihre Vielseitigkeit garantiert die Vitalität ihres Enthusiasmus. Sie ist auch die treibende Kraft hinter ihrer Neugier.

Seit Beginn eines musikalischen Abenteuers, das sich mehrere Jahre lang ausschließlich auf Live-Aufführungen der vollständigen Bach-Kantaten in Genf mit drei Konzerten pro Saison konzentrierte, ist Gli Angeli Genève der Schauplatz für Begegnungen zwischen einigen der berühmtesten Sänger und Instrumentalisten der internationalen Barockszene und jungen Absolventen der Musikhochschulen von Basel, Lyon, Lausanne und Genf.

Seit der Veröffentlichung seiner ersten beiden CDs in den Jahren 2009 und 2010, die zahlreiche Kritikerpreise gewannen, ist das Ensemble international bekannt und gibt nun sieben oder acht Konzerte pro Saison in Genf, zum einen im Rahmen seiner Reihe „Complete Bach Cantatas“, einer Reihe von jährlichen Konzerten in der Victoria Hall, zum anderen seit September 2017 in einer neuen vollständigen Reihe, die Haydns Symphonien gewidmet ist. Das Ensemble ist in der Schweiz und im Ausland gleichermaßen gefragt für Aufführungen nicht nur von Bach, sondern auch von Tallis, Josquin, Schein, Schütz, Johann Christoph Bach, Weckmann, Buxtehude, Rosenmüller, Haydn, Mozart und anderen. In den letzten Spielzeiten war Gli Angeli Genève beim Utrecht Festival und den Thüringer Bachwochen, residiert und trat auch in Basel, Zürich, Luzern, Barcelona, Nürnberg, Bremen, Stuttgart, Brüssel, Mailand, Breslau, Paris, Ottawa, Vancouver, Amsterdam und Den Haag auf. Gli Angeli Genève ist regelmäßiger Gast beim Festival de Saintes, beim Utrecht Festival, beim Musikfest Bremen oder beim Bach Festival Vancouver. Das Ensemble gab 2017 sein Debüt am Grand Théâtre in Genf und 2019 am KKL in Luzern.

Die vorletzte Aufnahme von Gli Angeli Genève für Claves, Sakrale Musik des 17. Jahrhunderts in Breslau, gewann 2019 den ICMA-Preis für die beste Vokalaufnahme mit Barockmusik des Jahres, und seine neueste Aufnahme, Die Matthäus-Passion von Johann Sebastian Bach, wird sowohl vom Publikum als auch von der Kritik in der Schweiz und weltweit begeistert aufgenommen.

Übersetzt aus dem Englischen mit www.DeepL.com/Translator

REVIEWS

“This studio recording of Bach’s greatest work, though one he only ever heard in his imagination, is notable for its transparent textures due to MacLeod’s decision to limit his singers to ten – a decision taken when Gli Angeli Genève was founded in 2005. In his booklet note MacLeod persuasively argues that such restrictions are not undertaken for strict historical authenticity – other reasons pertain, including placing all the singers in front of the instrumentalists, as would have occurred in the Thomaskirche in Bach’s day. On the recording this has the benefit of foregrounding the text and thereby to an extent solving many of the balance issues that occur in a conventional set-up. [..]” -Philip Reed, August 2021

« [..] Ansonsten punktet sie mit ihrer technischen Perfektion und ihrer musikalischen Homogenität. MacLeod geht es mehr um analytische Klarheit als um spirituelle Überhöhung; dementsprechend direkt und zügig ist sein Ansatz. Von den durchweg exzellenten Instrumentalsoli ist Leila Schayeghs Geigenspiel im „Laudamus te“ besonders hervorzuheben. » - Matthias Hengelbrock, September 2021

« [..] Dans cet opus, Stephan MacLeod et son ensemble Gli Angeli Genève abordent la messe avec dix chanteurs au total. Bach faisait pareil pour ses cantates de sorte à favoriser la parole à l'orchestre. Les voix s'épanouissent et sont soutenues admirablement par l'orchestre. [..] » - Septembre 2021

“Gli Angeli Genève perform the Mass in B minor with 10 singers (six concertists and four ripienists) and an orchestra of 27 players, each section led by outstanding musicians. Director (and bass) Stephan MacLeod enthuses that two singers on each line in the choruses, placed in front of the orchestra instead of behind it, is ‘more individualised, both in sound and interpretation … their respective timbres express their happiness and pleasure in letting music speak for itself’. [..] Overall, Gli Angeli Genève’s performance is characterised by swift momentum, crisp articulation and benevolent attention to detail.” - David Vickers, July 2021

« [..] Nach der famosen Matthäus-Passion vor einem Jahr nun eine h-Moll-Messe vom selben Kaliber: Ein Plädoyer für die schlanke Vokalbesetzung, ohne ideologische Verengung oder argumentativen Schaum vor dem Mund. Im Gegenteil: Ein funkensprühendes Erlebnis hochstehender Musikalität und stupenden Vermögens. Stephan MacLeod und sein Ensemble Gli Angeli Genève treten seit längerer Zeit vernehmlich als – vielleicht weithin nicht genug geschätzte – Bach-Kraft von Rang hervor. Dazu ist es ein wunderbares künstlerisches Lebenszeichen aus dem düsteren Corona-Herbst 2020. » - Dr. Matthias Lange, Mai 2021

« Interview. Il y a un an, Stephan MacLeod émouvait déjà dans Bach. La Passion selon saint Matthieu de l’ensemble Gli Angeli Genève faisait exploser les compteurs des téléchargements de la maison Claves. Une période de confinement en chasse une autre: il faut aujourd’hui encore se contenter de captations ou d’enregistrements en ce temps de Pâques. Mais Bach est toujours là qui nous tient la main, nous console et nous rassure de la beauté du monde. Interview du chef, qui offre ce printemps la Messe en si mineur. [..] » - Elisabeth Hass, avril 2021

“[..] Emotions are relegated to the background, instead much emphasis is placed on an objective and therefore very academic interpretation, which at best can please those who like an intellectual and professorial Bach.” - Alain Steffen, mars 2021

“[..] This is a creation of a very high level of interpretation, carefully thought out and carefully realised in the context of historical performance practices and the use of appropriate instrumentation, as evidenced by the very person of the ensemble's conductor and bass player, Stephen MacLeod, an artist who researches the lesser-known Baroque repertoire. [..] If I had to characterise this recording in a few words or one sentence, I would use the following words: beautiful, honest and modest. There are many fine recordings of this repertoire, more or less famous, spectacular and exciting, but by communing with the creation of the singers and the ensemble of Gli Angeli Genève under the direction of Stephan MacLeod, I was able not only to relax but also to comfort my mind, my heart and my soul. [..]” - Paweł Chmielowski, August 2021

“[..] The smaller forces in this new recording give a lovely transparency to the overall sound, beneficial in such compositional complexity, and an intimacy missing in recordings using greater numbers. The string players use period instruments, adding to the clarity of texture. Ensemble work throughout is exceptional. The booklet lists the choir and orchestra on the front and photos of the performers are included. The comprehensive introduction is in three languages, but the Latin text is only translated into French. [..]” - Patrice Connolly, April 2022

« [..] Aber gerade deswegen ruft es Begeisterung hervor, wenn es einem erfahrenen Interpreten wie Stephan MacLeod gelingt, mit höchst sorgfältig ausgewählten Musikerinnen und Musikern ein Ensemble zu formieren, das den „Beinahe-Normalfall“ einer entsprechend routinierten Darbietung nochmals deutlich überbietet. MacLeod selbst leuchtet voran in der fordernden Doppelaufgabe des Vokalisten und Ensembleleiters. Zur vokalen Leistung gehört nicht zuletzt auch die brillante Bewältigung der beiden in der Tessitura so verschiedenen Bassarien. Zu ihm gesellen sich hervorragende Sängerinnen und Sänger, die gerade auch in der heiklen Zwei-pro-Stimme-Besetzung der Chorsätze eine erstaunliche Homogenität zu erzeugen verstehen. Gemeinsam mit den gleichermaßen brillanten Instrumentalistinnen und Instrumentalisten bringen sie es zu einer geschmeidigen Eleganz und filigranen Transparenz des Klanges, die ihresgleichen sucht. [..] » - Michael Wersin, Mai 2021

« Avec la Messe en si, la formation poursuit avec pertinence son exploration de Bach en s’attaquant à un monument. [..] » - Rocco Zacheo, avril 2021

« [..] Es gibt unendlich viele Aufnahmen der h-Moll-Messe. Eine neue lässt jetzt aufhorchen: Das Ensemble Gli Angeli Genève unter Leitung des mitsingenden Bassisten Stephan McLeod hat eine wirklich überzeugende und berückende Einspielung von Bachs Opus ultimum vorgelegt. [..] Diese CD sei allen, die Bach lieben, dringlichst empfohlen, egal wie viele Aufnahmen des exzeptionellen Werkes bereits im Regal stehen – und Erstlingen in Sachen h-Moll-Messe sowieso. Und da es ein Werk für alle (Kirchenjahres-)Zeiten ist, eignet es sich auch trefflich dafür, unter dem Christbaum zu liegen. » - Reinhard Mawick, November 2022

Return to the album | Read the booklet | Composer(s): Johann Sebastian Bach | Main Artist: Stephan MacLeod